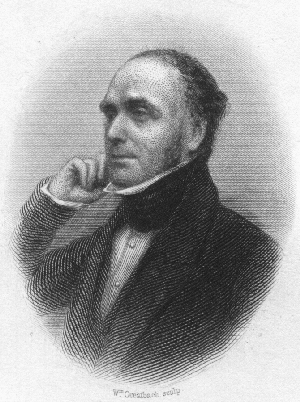

JOHN ROBY

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Traditions of Lancashire, Volume 1 (of 2)

Author: John Roby

Release Date: March 7, 2005 [eBook #15271]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TRADITIONS OF LANCASHIRE, VOLUME 1 (OF 2)***

"I know I have herein made myself subject unto a world of judges, and am likest to receive most controulment of such as are least able to sentence me. Well I wote that the works of no writers have appeared to the world in a more curious age than this; and that, therefore, the more circumspection and wariness is required in the publishing of anything that must endure so many sharp sights and censures. The consideration whereof, as it hath made me all the more needy not to displease any, to hath it given not the less hope of pleasing all."

| ADVERTISEMENT TO FIFTH EDITION | IX |

| PUBLISHERS' PREFACE TO FOURTH EDITION | X |

| MEMOIR OF THE AUTHOR | XII |

| PREFACE TO FIRST SERIES | XVI |

| PREFACE TO SECOND SERIES | XVIII |

| INTRODUCTION TO SECOND SERIES | XIX |

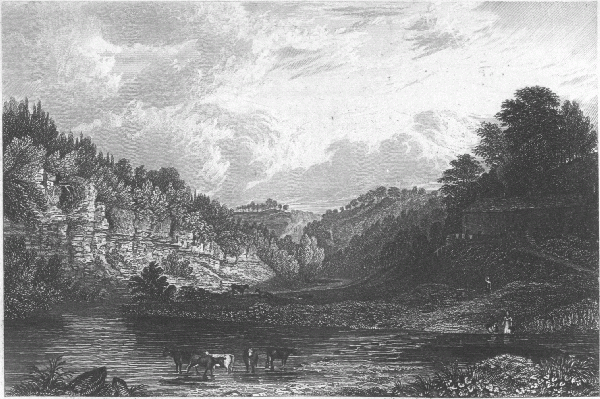

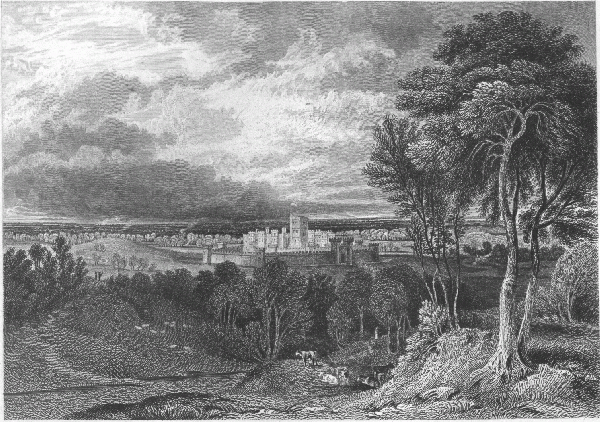

| MAB'S CROSS, WIGAN | To face page | 25 |

| BURSCOUGH ABBEY | 52 | |

| RADCLIFFE TOWER | 106 | |

| WHALLEY ABBEY | 111 | |

| HORNBY CASTLE | 137 | |

| COLLEGIATE CHURCH, MANCHESTER | 208 | |

| TYRONE'S BED, NEAR ROCHDALE | 220 | |

| HOGHTON TOWER | 247 | |

| EAGLE CRAG, VALE OF TODMORDEN | 284 | |

| LATHOM HOUSE | 311 | |

| SOUTH PORT | 363 | |

| INCE-HALL, NEAR WIGAN | 385 | |

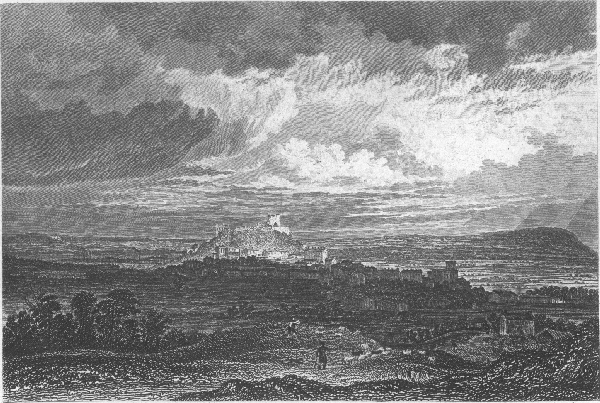

| CLITHEROE CASTLE | 402 |

The Fourth Edition of the "TRADITIONS OF LANCASHIRE" was published five years ago, and the whole of the impression was ordered from the publishers before it had left the printers' hands. Owing to the difficulty in obtaining copies, it has been suggested that a re-issue, in a cheap form, is a desideratum, and the present volumes are the result. This is the only Complete Edition (except the Fourth, from which it is an unabridged reprint), of Roby's Traditions—several Legendary Tales being incorporated which were not included in any of the earlier copies of the work.

November 1871.

Roby's "TRADITIONS OF LANCASHIRE" having long been out of print—stray copies commanding high prices—it has been determined to republish the whole in a more compact and less costly form. This, the fourth and the only complete edition, includes the First Series of twenty tales, published in two volumes (1829, demy 8vo, £2, 2s.; royal 8vo, with proofs and etchings, £4, 4s.); the Second Series, also of twenty tales, in two volumes (1831, 8vo, £2, 2s., &c.); and three additional stories from his Legendary and Poetical Remains, first published after his death (1854, post 8vo, 10s. 6d.)[1] In the two volumes now presented the reader will possess not only the whole of the contents of both series, in four volumes, at one-fourth of the price of the original publication, but also three additional stories from the posthumous volume, with a memoir, a portrait, &c.

From deference to a strongly-expressed feeling that the work should be printed without any abridgment, omission, or alteration, and the text preserved in its full integrity, it has been decided to reprint it entire; and consequently various inaccuracies in the original editions have been left untouched. Two or three of the most important may be corrected here.

In the tale of "The Dead Man's Hand," Mr Roby seems to have been led by false information into some errors reflecting on the character and memory of a devout and devoted Roman Catholic priest, known as Father Arrowsmith. Mr Roby states that he was executed at Lancaster "in the reign of William III.;" that "when about to suffer he desired his right hand might be cut off, assuring the bystanders that it would have power to work miraculous cures on those who had faith to believe in its efficacy," and, denying that Father Arrowsmith suffered on account of religion, Mr Roby adds that "having been found guilty of a misdemeanour, in all probability this story of his martyrdom and miraculous attestation to the truth of the cause for which he suffered, was contrived for the purpose of preventing any scandal that might have come upon the Church through the delinquency of an unworthy member."

What, then, are the facts, as far as they have been investigated? The Father Edmund Arrowsmith who suffered death at Lancaster was born at Haydock in Lancashire[2] in 1585, and he suffered death in August 1628 (4th Charles I.), sixty years before William III. ascended the English throne. The mode of execution was not that of capital punishment for the offence committed, but rather that imposed by the laws for treason and for exercising the functions of a Roman Catholic priest. He was hanged, drawn, and quartered, and his head and quarters were fixed upon poles on Lancaster Castle. It was in this dismemberment that the hand became separated, and it was secretly carried away by some sorrowing member of his communion, and its supposed curative power was afterwards discovered and made known.[3] Mr Roby cites no authority for this contradiction of the original tradition. The judge who presided at the trial was Sir Henry Yelverton of the Common Pleas, who died on the 24th January 1629.

In the Tradition of "The Dule upo' Dun," Mr Roby states that a public-house having that sign stood at the entrance of a small village on the right of the highway to Gisburn, and barely three miles from Clitheroe. When Mr Roby wrote the public-house had been long pulled down; it had ceased to be an inn at a period beyond living memory; though the ancient house, converted into two mean, thatched cottages, stood until about forty years ago. But the site of the house is in Clitheroe itself, little more than half a mile from the centre of the town, and on the road, not to Gisburn, but to Waddington.[4]

It only remains to add that the illustrations to the present edition comprise not only all the beautiful plates (engraved by Edward Finden, from drawings by George Pickering) of the original edition, which have been much admired as picturesque works of art, but also all the wood-engravings (by Williams, after designs by Frank Howard) which have appeared in any former edition, and which constituted the sole embellishments of the three-volume editions. To these is now first added the fine portrait of Mr Roby from the posthumous volume.

[1] The First Series includes all the Traditions beginning with "Sir Tarquin" and ending with "The Haunted Manor-House;" the Second Series comprises all the Tales from "Clitheroe Castle" to "Rivington Pike," both included; and the three Tales now first incorporated are—"Mother Red-Cap, or the Rosicrucians;" "The Death Painter, or the Skeleton's Bride;" and "The Crystal Goblet."

[2] His mother was a daughter of the old Lancashire family of Gerard of Bryn.

[3] These dates and facts will be found in the Missionary Priests of Bishop Challoner, who wrote about 1740 (2 vols. 8vo., Manchester, 1741-2), naming as his authority a manuscript history of the trial, and a printed account of it published in 1629. His statements are confirmed by independent testimony. See Henry More's Historia-Provinciæ Anglicaæ Societatis Jesu, book x. (sm. fol. St Omer's, 1660). Also Tanner's Societas Jesu, &c., p. 99 (sm. fol. Prague, 1675). Neither Challoner nor the MS. account, nor either of the authors just quoted, says one word of Father Arrowsmith's alleged speech about the hand.

[4] See Mr Wm. Dobson's Rambles by the Ribble, 1st Series, p. 137.

The late John Roby was born at Wigan on the 5th January 1793. From his father, Nehemiah Roby, who was for many years Master of the Grammar-School at Haigh, near Wigan, he inherited a good constitution and unbended principles of honour and integrity. From the family of his mother, Mary Aspall, he derived the quick, impressible temperament of genius, and the love of humour which so conspicuously marks the Lancashire character. He was the youngest child. His thirst for knowledge was early and strongly manifested. Being once told in childhood not to be so inquisitive, his appeal ever after was, "Inquisitive wants to know." As he grew up into boyhood, surrounded by objects to which tradition had assigned her marvellous stories, they sank silently but indelibly into his mind. In his immediate vicinity were Haigh Hall and Mab's Cross, the scenes of Lady Mabel's sufferings and penance—the subject of one of his earliest tales. Almost within sight of the windows lay the fine range of hills of which Rivington Pike is a spur. In after-life he recalled with pleasure the many sports in that district which were the haunts of his early days, and the scenes of the legends he afterwards embodied. While yet a child he regularly took the organ in a chapel at Wigan during the Sunday service. He also early excelled in drawing, and after he had commenced the avocations of a banker the use of the pencil was a favourite recreation. His first prose composition, at the age of fifteen years, took a prize in a periodical for the best essay on a prescribed subject, by young persons under a specified age. Thus encouraged, poetry, essay, tale, were all tried, and with success. In his eighteenth or nineteenth year he received a silver snuff-box, inscribed, "The gift of the Philosophic Society, Wigan, to their esteemed lecturer and worthy member."

Mr Roby first appeared before the public as a poet; publishing in 1815, "Sir Bertram, a poem in six cantos." Another poem quickly followed, entitled "Lorenzo, a tale of Redemption." In 1816, he married Ann, the youngest daughter of James and Dorothy Bealey, of Derrikens, near Blackburn, by whom he had nine children, three of whom died in their infancy. His next publication was "The Duke of Mantua," a tragedy, which appeared in 1823, passed through three or four editions in a short time, and after being long out of print, was included in the posthumous volume of Legendary Remains. In the summer of that year he made an excursion in Scotland, visiting "the bonnie braes o' Yarrow" in company with James Hogg, the Ettrick Shepherd. The literary leisure of the next six years was occupied in collecting materials for the Traditions of Lancashire, and in weaving these into tales of romantic interest. In this task he received the most courteous assistance from several representatives of noble houses connected with the traditions of the county; particularly from the late Earl and Countess of Crawford and Balcarres, and also from the late Earl of Derby.

The first series of The Traditions of Lancashire appeared in 1829, in two volumes (including twenty tales), illustrated by plates. The reception of the work equalled Mr Roby's most sanguine expectations; and a second edition was called for within twelve months. The late Sir Francis Palgrave, in a letter to Mr Roby, dated 26th October 1829, thus estimates the work:—

"As compositions, the extreme beauty of your style, and the skill which you have shown in working up the rude materials, must entitle them to the highest rank in the class of work to which they belong.... You have made such a valuable addition, not only to English literature, but to English topography, by your collection—for these popular traditions form, or ought to form, an important feature in topographical history—that it is to be hoped you will not stop with the present volumes."

The second series of the "Traditions," consisting also of two volumes (including twenty tales), uniform with the first, was published in 1831, and met with similar success. Both series were reviewed in the most cordial manner by the leading periodicals of the day; while they were more than once quoted by Sir Walter Scott, who characterised the whole as an elegant work. In the production of these tales, Mr Roby's practice was to make himself master of the historical groundwork of the story, and as far as possible of the manners and customs of the period, and then to commence composition, with Fosbroke's Encyclopedia of Antiquities at hand, for accuracy of costume, &c. He always gave the credit of his style, which the Westminster Review termed "a very model of good Saxon," to his native county, the force and energy of whose dialect arises mainly from the prevalence of the Teutonic element. "The thought digs out the word," was his favourite saying, when the exact expression he wanted did not at once occur. In these "Traditions" his great creative power is conspicuous; about two hundred different characters are introduced, no one of which reminds the reader of another, while there is abundant diversity of both heroic and comic incident and adventure. A gentleman, after reading the "Traditions," remarked that for invention he scarcely knew Mr Roby's equal. All these characters, it should be stated, are creations: not one is an idealised portrait. The short vivid descriptions of scenery scattered throughout are admirable. Each tale is, in fact, a cabinet picture, combining history and romance with landscape. Mr Roby excelled in depicting the supernatural; and one German reviewer declared his story of Rivington Pike to be "the only authentic tale of demoniacal possession the English have."

In 1832, Mr Roby visited the English lakes, and recorded his impressions in lively sketches both with pen and pencil. In the spring of 1837, he made a rapid tour on the Continent, the notes and illustrative sketches of which were published in two volumes, under the title of Seven Weeks in Belgium, Switzerland, Lombardy, Piedmont, Savoy, &c. In 1840, Mr Roby again visited the Continent by a different route, making notes and sketches of what he saw. At the close of the year, he was engaged in preparing a new edition of the "Traditions," in a less expensive form. It was published in three volumes, as the first of a series of Popular Traditions of England; his intention being to follow up those of Lancashire with similar legends of Yorkshire, for which he wrote a few tales, which appeared in Blackwood's and Eraser's Magazines.

The principal literary occupation of the next four years appears to have been the preparation and delivery of lectures on various subjects in connection with literary and mechanics' institutions. In 1844, his health gave way, and for years he suffered severely. As a last resource he tried the water-cure at Malvern in the spring of 1847, and with complete success. In the summer of 1849, he again married—the lady who survived him, and to whose "sketch of his life" we are largely indebted in this brief memoir. In the two short years following this marriage—the two last of his life—he was busily engaged in writing and delivering lectures, visiting places which form the scenes of some of his latest legends, and in the composition of a series of tales intended to illustrate the influence of Christianity in successive periods, a century apart. Deferring that for the fourth century, he wrote six, bringing the series down to the close of the seventh century; when he determined on visiting Scotland. With his wife and daughter he embarked at Liverpool on board the steamer Orion for Glasgow, which ill-fated vessel struck on some rocks about one o'clock in the morning of the 18th June 1850, and went down. Mrs and Miss Roby were rescued after having been some time in the water, but of the husband and father only the corpse was recovered, and his remains were laid in his family grave in the burial-ground of the Independent Chapel, Rochdale, on Saturday, the 22d of that month.

Mr Roby was not more remarkable for his numerous and varied talents than for his warm and affectionate heart, rich imagination, great love of humour, and deep and earnest piety. He was a facile versifier, an elegant prose writer, an able botanist and physiologist. Possessing a fine ear, rich voice, and great musical taste, he not only took his vocal share in part-song, but wrote several melodies, which have been published. In one species of rapid mental calculation, or rather combination of figures—giving in an instant the sum of a double column of twenty figures in each row, or a square of six figures—he far excelled Bidder, the calculating boy. He was a skilful draughtsman, a clever mimic and ventriloquist, an excellent raconteur, an accomplished conversationist, ever fascinating in the select social circle, and always "tender and wise" in that of home. He was a man of genuine benevolence, a cordial friend, an affectionate husband and father, and a humble and devout Christian. His family crest was a garb or wheat-sheaf, with the motto, "I am ready;" and in his case—though his death was sudden and unexpected—illness and bereavement, mental and physical suffering—in short, the chastenings and discipline of life, had done their work. His "sheaf" was "ready for the garner."

October 1866.

[5] This Memoir has been almost wholly derived from the "Sketch of the Literary Life and Character of John Roby," written by his widow, and occupying 117 pages of the posthumous volume of his Legendary and Poetical Remains.

A preface is rarely needed, generally intrusive, and always tiresome—seldom read, more seldom desiderated: a piece of egotism at best, where the author, speaking of himself, has the less chance of being listened to. Yet—and what speaker does not think he ought to be heard?—the author conceives there may be some necessity, some reason, why he should step forward for the purpose of explaining his views in connection with the character and design of the following pages.

In the northern counties, and more particularly in Lancashire, the great arena of the STANLEYS during the civil wars—where the progress and successful issue of his cause was but too confidently anticipated by CHARLES STUART, and the scene especially of those strange and unholy proceedings in which the "Lancashire witches" rendered themselves so famous—it may readily be imagined that a number of interesting legends, anecdotes, and scraps of family history, are floating about, hitherto preserved chiefly in the shape of oral tradition. The antiquary, in most instances, rejects the information that does not present itself in the form of an authentic and well-attested fact; and legendary lore, in particular, he throws aside as worthless and unprofitable. The author of the "TRADITIONS OF LANCASHIRE," in leaving the dry and heraldic pedigrees which unfortunately constitute the great bulk of those works that bear the name of county histories, enters on the more entertaining, though sometimes apocryphal narratives, which exemplify and embellish the records of our forefathers.

A native of Lancashire, and residing there during the greater part of his life, he has been enabled to collect a mass of local traditions, now fast dying from the memories of the inhabitants. It is his object to perpetuate these interesting relics of the past, and to present them in a form that may be generally acceptable, divested of the dust and dross in which the originals are but too often disfigured, so as to appear worthless and uninviting.

Tradition is not an unacceptable source of historical inquiry; and the writer who disdains to follow these glimmerings of truth will often find himself in the dark, with nothing but his own opinions—the smouldering vapour of his own imagination—to guide him in the search.

The following extract from a German writer on the subject sufficiently exemplifies and illustrates the design the author has generally had before him in the composition and arrangement of the following legends:—

"Simple and unimportant as the subject may at first appear, it will be found, upon a nearer view, well worth the attention of philosophical and historical inquirers. All genuine, popular Tales, arranged with local and national reference, cannot fail to throw light upon contemporary events in history, upon the progressive cultivation of society, and upon the prevailing modes of thinking in every age. Though not consisting of a recital of bare facts, they are in most instances founded upon fact, and in so far connected with history, which occasionally, indeed, borrows from, and as often reflects light upon, these familiar annals, these more private and interesting casualties of human life.

"It is thus that popular tradition, connected with all that is most interesting in human history and human action, upon a national scale—a mirror reflecting the people's past worth and wisdom—invariably possesses so deep a hold upon its affections, and offers so many instructive hints to the man of the world, to the statesman, the citizen, and the peasant.

"Signs of approaching changes, no less in manners than in states, may likewise be traced, floating down this popular current of opinions, fertilising the seeds scattered by a past generation, and marking by its ebbs and flows the state of the political atmosphere, and the distant gathering of the storm.

"National traditions further serve to throw light upon ancient and modern mythology; and in many instances they are known to preserve traces of their fabulous descent, as will clearly appear in some of the following selections. It is the same with those of all nations, whether of eastern or western origin, Greek, Scythian, or Kamtschatkan. And hence, among every people just emerged out of a state of barbarism, the same causes lead to the production of similar compositions; and a chain of connection is thus established between the fables of different nations, only varied by clime and custom, sufficient to prove, not merely a degree of harmony, but secret interchanges and communications."

A record of the freaks of such airy beings, glancing through the mists of national superstition, would prove little inferior in poetical interest and association to the fanciful creations of the Greek mythology. The truth is, they are of one family, and we often discover allusions to the beautiful fable of Psyche or the story of Midas; sometimes with the addition, that the latter was obliged to admit his barber into his uncomfortable secret. Odin and Jupiter are brothers, if not the same person; and the northern Hercules is often represented as drawing a strong man by almost invisible threads, which pass from his tongue round the limbs of the victim, thereby symbolising the power of eloquence. Several incidents in the following tales will be recognised by those conversant with Scandinavian literature, thus adding another link to the chain of certainty which unites the human race, or at any rate that part of it from which Europe was originally peopled, in one original tribe or family.

A work of this nature, embodying the material of our own island traditions, has not yet been attempted; and the writer confidently hopes that these tales may be found fully capable of awakening and sustaining the peculiar and high-wrought interest inherent in the legends of our continental neighbours. Should they fail of producing this effect, he requests that it may be attributed rather to his want of power to conjure up the spirits of past ages, than to any want of capabilities in the subjects he has chosen to introduce.

To the local and to the general reader—to the antiquary and the uninitiated—to the admirers of the fine arts and embellishments of our literature, he hopes his labours will prove acceptable; and should the plan succeed, not Lancashire alone, but the other counties, may in their turn become the subject of similar illustrations. The tales are arranged chronologically, forming a somewhat irregular series from the earliest records to those of a comparatively modern date. They may in point of style appear at the commencement stiff and stalwart, like the chiselled warriors, whose deeds are generally enveloped in a rude narrative, hard and ponderous as their gaunt and grisly effigies. The events, however, as the author has found them, gradually assimilate with the familiar aspects and everyday affections of our nature—subsiding from the stern and repulsive character of a barbarous age into the usual forms and modes of feeling incident to humanity—as some cold and barren region, where one stunted blade of affection can scarce find shelter, gradually opens Out into the quiet glades and lowly habitudes of ordinary existence.

The author disclaims all pretensions to superior knowledge. He would not even arrogate to himself the name of antiquary. Some of the incidents are perhaps well known, being merely put into a novel and more popular shape. The spectator is here placed upon an eminence where the scenes assume a new aspect, new combinations of beauty and grandeur being the result of the vantage ground he has obtained. Nothing more is attempted than what others, with the same opportunities, might have done as well—perhaps better. When Columbus broke the egg—if we may be excused the arrogance of the simile—all that were present could have done the same; and some, no doubt, might have performed the operation more dexterously.

1st October 1829.

In presenting another and concluding series of Lancashire Traditions to the public, the author has to express his thanks for the indulgence he has received, and the spirit of candour and kindness with which this attempt to illustrate in a novel manner the legends of his native county has been viewed by the periodical press.

To his numerous readers, in the capacity of an author, he would say Farewell, did not the "everlasting adieus," everlastingly repeated, warn him that he might at some future time be subject to the same infirmity, only rendered more conspicuous by weakness and irresolution.

Rochdale, October 1831.

No method has yet been discovered for preserving the recollection of human actions and events precisely as they have occurred, whole and unimpaired, in all their truth and reality. Time is an able teacher of causes and qualities, but he setteth little store by names and persons, or the mould and fashion of their deeds. The pyramids have outlived the very names of their builders. "Oblivion," says Sir Thomas Browne, "blindly scatters her poppies. Time has spared the epitaph of Adrian's horse—confounded that of himself!"

Few things are so durable as the memory of those mischiefs and oppressions which Time has bequeathed to mankind. The names of conquerors and tyrants have been faithfully preserved, while those from whom have originated the most useful and beneficial discoveries are entirely unknown, or left to perish in darkness and uncertainty. We should not have known that Lucullus brought cherries from the banks of the Phasis but through the details of massacre and spoliation—the splendid barbarities of a Roman triumph. In some instances Time displays a fondness and a caprice in which the gloomiest tyranny is seen occasionally to indulge. The unlettered Arab cherishes the memory of his line. He traces it unerringly to a remoter origin than could be claimed or identified by the most ancient princes of Europe. In many instances he could give a clearer and a higher genealogy to his horse. But that which Time herself would spare, the critic and the historian would demolish. The northern barbarians are accused of an exterminating hostility to learning. It never was half so bitter as the warfare which learning displays against everything of which she herself is not the author. A living historian has denied that the poems of Ossian had any existence save in the conceptions of Macpherson, because he condescendingly informs us, "Before the invention or introduction of letters, human memory is incapable of any faithful record which may be transmitted from age to age."

The account which Macpherson gave may be a fiction, but it is admitted by those who know the native Scotch and Irish tongues, and have dwelt where no other language is spoken, that there are poems which have been transmitted from generation to generation (orally it must be, since letters are either entirely unknown or are comparatively of recent introduction), the machinery of which prove them to have been invented about the time when Christianity was first preached in these islands.

Tradition may well be named the eldest daughter of Time, and nursing-mother of the Muses—the fruitful parent of that very learning which would, in the cruel spirit of its pedantry and malice, make her the sacrifice while it lays claim to the inheritance. What is learning but a laborious, often ill-drawn, and almost invariably partial deduction from facts which tradition has first collected? When we consider in whose hands learning has been, almost ever since its creation; the uses which have been made of it by priests and politicians; by poets, orators, and flatterers; by controversialists and designing historians;—how commonly has it been perverted to abuse the very senses of mankind, and to give a bias to their thoughts and feelings, only to mislead and to betray! Let the evidence be well compared, and a view taken of the respective amounts of doubt and certainty which appertain to human history as it appears in written records; and it will be seen that, to verify any given fact, so as to prevent the possibility of doubt, we must throw aside our reverence for the scholar's pen and the midnight lamp, which seem, like the faculty of speech, only given to men, as the witty Frenchman observed, "to conceal their thoughts." This comparative process is precisely what has been adopted by M.L. Petit Radel in his new theory upon the origin of Greece. "Not satisfied with the mythological equivocation and contradictory statements which till now have perplexed the question, after a residence of ten years this learned man returns with a new theory, which would destroy all our received ideas, and carry the civilisation and cradle of the Greeks much beyond the time and place that have till now been supposed. It is their very architecture that M. Petit Radel interrogates, and its passive testimony serves as a basis to his system. He has visited, compared, and meditated on the unequivocal vestiges of more than one hundred and fifty antique citadels, altogether neglected by the Greek and Roman authors. Their form and construction serve him, with the aid of ingenious reasoning, to prove that Greece was civilised a long time before the arrival of the Egyptian colonies. He does not despair of tracing back the descent of the Greeks to the Hyperborean nations, always by the analogy of their structures, which, by a singular identity, are found also among the Phoenicians. The Institute have pronounced the following judgment upon his theory:—'If the developments which remain to be given to us suffice to gain the votes of the learned, and induce them to adopt this theory as demonstrated truth, M. L. Petit Radel may flatter himself with having made in history a discovery truly worthy to occupy a place in the progress of human genius.'"

Thus the very time in which a living historian of England has chosen to inflict an impotent blow, from the leaden sceptre of Johnsonian criticism, upon all facts which claim an existence anterior to the invention of books, appears pregnant with a discovery of a method of investigating the most remote eras, which presupposes an inherent spirit of fallacy and falsehood in all written records of their existence.

About three hundred years after the era of the Olympiads, the first date of authentic history, Herodotus astonished his countrymen by the writings he brought forth. Who kept the records out of which his work was elaborated ere he was ready to stamp the facts with the only seal which our modern historians will acknowledge or allow? Tradition doubtless was his guide, which the learned themselves complain of as the source of what they term his errors and his fables. But the voice of tradition has often reinstated his claims to our belief, where it had been suspended either by ignorance or pretensions to superior knowledge. A modern traveller found, in one of the isles of the Grecian Archipelago, undoubted vestiges of a state of society similar to that of the Amazons. The order of the sexes was wholly inverted. The wife ruled the husband, and his and her kindred, with uncontrolled and unsparing rigour, sanctioned and even commanded by the laws. Yet the very existence of any such people as the Amazons of ancient history has not only been questioned, but denied. Learning has proved it to be impossible.

The Marquess of Hastings told the Rev. Mr Swan, chaplain of the Cambrian, that he had found the germ of fact from which many of the most incredible tales in ancient history had grown during his stay in India. One instance only we would relate. A Grecian author mentions a people who had only one leg. An embassy from the interior was conducted into the presence of the viceroy, and he could by no persuasion prevail upon the obsequious minister to use more than one of his legs, though he stood during the whole of a protracted audience.

But there are other forces now drawing into the field to support the long-neglected claims of tradition. Etymology, which professed to settle doubts by an appeal to the elementary sounds of words, was banished from the politer and more influential circles of English learning by a decree as arbitrary as that pronounced on the poems of Ossian. It has come back with a new commission and under a new title;—Ethnography is the name given by our continental neighbours to this new science, which, in its future developments, may bring to light some of the most obscure and important circumstances affecting the human race, from its origin through every succeeding epoch of its existence. The distinguishing object of this inquiry is to identify the fortunes, migrations, and changes of the human family as to situation, policy, religion, agriculture, and arts, by comparing the terms supplied by or introduced into the language of any one country with the names of the same objects in every other. There would be no such thing as chance in nature could we know the laws which determine every separate accident. In like manner there will scarcely be any doubt respecting the primitive history of man when this new science shall have accumulated and revealed all the treasures which it may be enabled to appropriate. An agreement in the primitive term which any object of cultivation, physical or moral, bears among many different tribes, spread over many and far-distant regions, will be considered as the best evidence of one common origin. Disagreement in a similar case, accompanied with a great variety of terms of considerable dissonance, will be equally conclusive as to the object being indigenous or of a multifarious origin.

Already has Balbi, in his Ethnographic Atlas, given us a list of names and coincidences to an extent truly astonishing. Yet what is this, in fact, but a judicious use of Bacon's old but much-neglected rule of questioning nature about facts instead of theories—examining evidences ere rhetoric had made language one vast heap of implied falsehood?

In a court of inquiry we examine witnesses as to facts, not opinions. But the historian reads mankind in cities; the philosopher in the clouds. He who is anxious for the truth should look abroad on the plains or in the woods, where man's first prerogative, the giving of names, was exercised. His knowledge of nature must be wretchedly imperfect who thinks that no grand outline of truth can possibly exist in the dim records of human recollection ere the pen of the scholar was employed to depict the scenes that opinion or prejudice had created. How many pages of Clarendon's, Hume's, or even Robertson's history would be cancelled if we had access to all the recollections of each event, and the evidence of the unlettered vulgar who had witnessed the fact brought to our notice, even through the mouthpiece of tradition!

There is more truth than comes to the surface in that speech put into the lips of the father of lies by a late poet, where he says—

"The Bible's your book—history mine."

Savigny makes the same charge against one class of historians in his own country:—"However discordant," says he, "their other doctrines may appear, they agree in the practice of adopting each a particular system, and in viewing all historical evidence as so many proofs of its truth."

Were it not for that contempt we have already noticed as the offspring of pride and dogmatism, and which, in the administration of the republic of letters, has been entertained and openly proclaimed for every kind of history except that which its own acts may have originated, we should have been in possession of thousands of facts and notions now overlaid and lost irrecoverably to the philosopher and the historian.

The origin and the progress of nations, next after the school divinity of the Middle Ages, has occasioned the most copious outpouring of conjectural criticism. The simple mode of research suggested by the works of Verstegan, Camden, and Spelman would, long before this time, have made the early history of the British tribes as clear as it is now obscure. Analogies in the primary sounds of each dialect; similarity or difference in regard to objects of the first, or of a common necessity; rules or laws for the succession of property, which are as various as the tribes which overran the empire; the nature, agreement, or dissimilarity in religious worship with those vestiges of its ritual and celebration which, by the "pious frauds" and connivance of the early church, still lurk in the pastimes of our rural districts:—the new science of which we have spoken, by taking cognisance of these and all other existing sources of legitimate investigation, will settle the source and affinities of nations upon a plan as much superior to that of Grotius and his school as fact and reason exceed the guess-work of the theorist and the historian. Meantime we would cite a few examples that illustrate and bear more particularly on the subject to which our inquiries have been directed.

Nothing seems at first sight more difficult than to establish a community of origin between the gods of Olympus and those of the Scandinavian mythology. The attempt has often been made, and each time with increased success. Observe the process adopted in this interesting inquiry.

"Every country in Europe has invested its popular fictions with the same common marvels—all acknowledge the agency of the lifeless productions of nature; the intervention of the same supernatural machinery; the existence of elves, fairies, dwarfs, giants, witches, and enchanters; the use of spells, charms, and amulets, and all those highly-gifted objects, of whatever form or name, whose attributes refute every principle of human experience, which are to conceal the possessor's person, annihilate the bounds of space, or command a gratification of all our wishes. These are the constantly-recurring types which embellish the popular tale: which have been transferred to the more laboured pages of romance; and which, far from owing their first appearance in Europe to the Arabic conquest of Spain, or the migrations of Odin to Scandinavia, are known to have been current on its eastern verge long anterior to the era of legitimate history. The Nereids of antiquity, the daughters of the 'sea-born seer,' are evidently the same with the mermaids of the British and northern shores. The inhabitants of both are fixed in crystal caves or coral palaces beneath the waters of the ocean; they are alike distinguished for their partialities to the human race, and their prophetic powers in disclosing the events of futurity. The Naiads differ only in name from the Nixen of Germany and Scandinavia (Nisser), or the water-elves of our countrymen. Ælfric and the Nornæ, who wove the web of life, and sang the fortunes of the illustrious Helga, are but the same companions who attended Ilithyia at the births of Iamos and Hercules," the venerable Parcæ of antiquity.

The Russian Rusalkis are of the same family. The man-in-the-moon has found a circulation throughout the world. "The clash of elements in the thunder-storm was ascribed in Hellas to the rolling chariot-wheels of Jove, and in the Scandinavian mythology to the ponderous waggon of the Norwegian Thor."

To the above extract, which is taken from the excellent preface by the editor to Wharton's History of English Poetry, may be added the number of high peaks bearing the name of Tor or Thor, seen more especially on both coasts of Devonshire, and which are supposed to signalise the places of his worship.[6] From the same source may be derived affinities equally strong between the Highland Urisks, the Russian Leschies, the Pomeranian or Wendish Berstucs, and the Panes and Panisci who presided over the fields and forests of Arcadia. The mountains of Germany and Scandinavia are under the governance of a set of metallurgic divinities, who agree with the Cabiri, Hephæsti, Telchines, and Idæan Dactyli. The Brownies and Fairies are of the same kindred as the Lares of Latium. "The English Puck, the Scottish Bogle, the French Esprit Follet, or Goblin, the Gobelinus of monkish Latinity, and the German Kobold, are only varied names for the Grecian Kobalus, whose sole delight consisted in perplexing the human race, and calling up those harmless terrors that constantly hover round the minds of the timid." "The English and Scottish terms, 'Puck,' 'Bogle', are the same as the German 'Spuk' and the Danish 'Spogelse,' without the sibilant aspiration. These words are general names for any kind of spirit, and correspond to the 'pouk' of Piers Ploughman. In Danish 'spog' means a joke, trick, or prank, and hence the character of Robin Goodfellow. In Iceland Puki is regarded as an evil sprite; and in the language of that country, 'at pukra' means both to make a murmuring noise and to steal clandestinely. The names of these spirits seem to have originated in their boisterous temper—'spuken,' Germ. to make a noise: 'spog,' Dan. obstreperous mirth; 'pukke,' Dan. to boast, scold. The Germans use 'pochin' in the same figurative sense, though literally it means to strike, beat; and is the same with our poke."

However varied in name, the persons and attributes of these immaterial beings have no variance which will not readily be accounted for by the difference of climate, territorial surface, and any priority that one tribe had gained over another in the march of mind. The relics of such a system were much more abundant half-a-century ago, and many a tale of love and violence, garnished with the machinery of that mythos, might have been gleaned from the unwritten learning of the people. Who would expect to find amongst the rudest of the Irish peasantry—whose ancestors never knew the use of letters, and by whom, even down to living generations, the English tongue has not been spoken—a number of fictions, amongst the rest the tale of Cupid and Psyche—closely corresponding to that of the Greeks?[7] Who that has been a child does not recollect the untiring delight with which he listened to those ingenious arithmetical progressions, reduced to poetry, called "The House that Jack built," and the perils of "The Old Woman with the Pig?" Few even of those in riper years would suspect their Eastern origin. In the Sepher Haggadah there is an ancient parabolical hymn, in the Chaldee language, sung by the Jews at the feast of the Passover, and commemorative of the principal events in the history of that people. For the following literal translation we are indebted to Dr Henderson, the celebrated orientalist:—

The following is the interpretation by P.N. Leberecht, Leipzig, 1731.

"1.—The kid, which was one of the pure animals, denotes the Hebrews.

"The father, by whom it was purchased, is Jehovah, who represents himself as sustaining this relation to the Hebrew people.

"The two pieces of money signify Moses and Aaron, through whose mediation the Hebrews were brought out of Egypt.

"2.—The cat denotes the Assyrians, by whom the ten tribes were carried into captivity.

"3.—The dog is symbolical of the Babylonians.

"4.—The staff signifies the Persians.

"5.—The fire indicates the Grecian empire under Alexander the Great.

"6.—The water betokens the Roman, or the fourth of the great monarchies to whose dominion the Jews were subjected.

"7—- The ox is a symbol of the Saracens, who subdued Palestine, and brought it under the caliphate.

"8.—The butcher that killed the ox denotes the Crusaders, by whom the Holy Land was wrested out of the hands of the Saracens.

"9.—The angel of death signifies the Turkish power, by which the land of Palestine was taken from the Franks, and to which it is still subject.

"10.—The commencement of the tenth stanza is designed to show that God will take signal vengeance on the Turks, immediately after whose overthrow the Jews are to be restored to their own land, and live under the government of their long-expected Messiah."

To return to illustrations less remote, and of a more familiar nature:—

An ill-bred. Londoner calls a shilling a hog, and half-a-crown a bull. He little knows what havoc he is making with our modern theorists, who assert that nothing is worthy of belief, or ought to be relied upon, before the era of "legitimate" or written "history." These terms corroborate and identify themselves with the most ancient of traditionary customs, long ere princes had monopolised the surface of coined money with their own images and superscriptions. They are identical with the very name of money among the early Romans, which was pecunia, from pecus, a flock. Among the same people, it is well known, the word stipulatio signified the striking of a bargain, which was done by placing two straws, stipes, one across the other. The same mode is practised to this day in the Isle of Man, existing, in all probability, from a period earlier than the foundation of Rome itself. Is the coincidence accidental or traditional? If the latter, what a history it tells of the migration of the species!

How much might be written of amulets, cups, and horns of magical power, from the divining cup of Genesis to the Amalthean horns, and the goblet of Oberon, which he gave to Huon of Bordeaux, the supernatural power of which, passing into an hundred shapes of fiction, may be found in our baronial halls—a pledge, to a certain extent, like the invulnerability of Achilles, of the good fortune of its possessor. It is wonderful that Shakespeare, who is so happy in the verisimilitude of his fairy lore, and so apt to embellish his plot with its mythology, should not have thought of causing the king-making Earl of Warwick to lose the horn of that prodigious cow—no doubt one of those guardian pledges bestowed upon his family—by way of presage to his fall. Deer's antlers, there can be little doubt, were placed in the halls of our forefathers, a votive offering to the Diana of the Scandinavian Pantheon; as it was the custom in like manner to ornament the temples with the heads of sacrificial victims in the Greek and Roman worship. The eagerness of our sportsmen for the "brush," as the first trophy in the chase, has in all probability originated from the same propitiatory notion.

Few would expect to meet with fragments of the worship of Juno in the racing of country girls for an inner garment, and the hunting of the pig with his tail greased; yet practised, but rapidly becoming obsolete, in wakes and other pastimes from Scotland to the Land's End.

Thus far we have examined tradition by the test of positive experience. There is still a gleaning of poetry which might be culled, in some few districts, from the "lyre of the unlettered muse." There are songs scattered up and down our own and the neighbouring counties among the population least affected by the spread of literature which are of great antiquity, and are not to be found in any books or writings now extant. A few of these might be gathered in; while to some, who love the tone and humour of the old ballads, they would be an acquisition of great value. But the intercourse between master and man, between town and country, and even amongst the learned themselves, becomes so cold and repulsive, either from increasing refinement or reserve, that there seems little hope of our finding any one who will take the trouble to collect them, or a sufficient number of real admirers of these relics who would come forward to ensure a suitable reward for the labour. We are sorely disgraced among foreigners for inattention to the course and progress of our own learning. No work exists, like those which illustrate and embellish the French, Italian, and German literature, which professes to give a summary view of its history. The knowledge of its antiquities, its customs, manners, laws, modes of feeling, and pursuits, except in the instances before mentioned, and a few other praiseworthy exceptions, have been shamefully obscured by an eagerness for supporting a system, the ridiculous rivalry of pretence, and by the discredit thrown upon such labours by modern pedantry. A new version of Camden, rectified by all the discoveries subsequent to his time;—that which is found useless or erroneous left out, and the work enlightened by new researches, entered into by a number of inquirers equal in all respects to the task, and exerted over every part of the country, would very much aid the cause of learning and the future progress of our knowledge.

The following traditions, we would fain hope, will not be found quite destitute of utility. They are some addition to our existing stock of knowledge, either as illustrating English history, manners, and customs now obsolete, or as a collection of legends, having truth for their basis, however disfigured in their transmission through various modifications of error, the natural obscurity arising from distance, and the distorted media through which they must necessarily be viewed. Perhaps a main source of this inaccuracy arises from the many and heterogeneous uses to which the breakings up, the fragments of tradition have been subjected and applied. Like those detached yet beautiful remnants of antiquity, built up with other and absolutely worthless materials in the rude structures of the barbarian by whom they have been disfigured, traditions are generally presented to us torn from their original connection with edifices once renowned for beauty and magnificence. It is our wish, as it has been our aim, to rescue these ruins from degradation and decay. Gathered from many an uninviting heap of chaotic matter, they are now presented in a different form, and under a more popular aspect. We cannot pretend to say that we have invariably assigned to them their true origin, or that their real character and position have been ascertained. Still, we would hope, that, as relics of the past rescued from the oblivion to which they were inevitably hastening, they are not either an uninteresting or inelegant addition to the literature of our country.

[6] "They worshipped fire as the representative of the Deity, which they kept continually burning on the tops of their highest mountains."—Foreign Quarterly Review, No. XV.: Art. "Popular Poetry," p. 77.

[7] That Ireland has not always presented so degrading and uncivilised an aspect as now exists in that unhappy country, there is abundant testimony to convince the most incredulous. Camden, an author by no means partial on this score, says:—"The Irish scholars of St. Patrick profited so notably in Christianity that, in the succeeding age, Ireland was termed 'Sanctorum Patria.'" Their monks so excelled in learning and piety, that they sent whole flocks of most holy men into all parts of Europe, "who were founders of the most eminent monasteries both there and in Britain."

"A residence in Ireland," says a learned British writer, "like a residence now at an university, was considered as almost essential to establish a literary character." By common consent, and as a mark of pre-eminence, Ireland obtained the title of Insula Sanctorum et Doctorum.

At the Council of Constance, in 1417, the ambassadors from England were not allowed to rank or take any place as the ambassadors of a nation. The point being argued and conceded, that they were tributaries only to the Germans, "they claimed their rank from Henry being monarch of Ireland only, and it was accordingly granted."—O'Halloran.

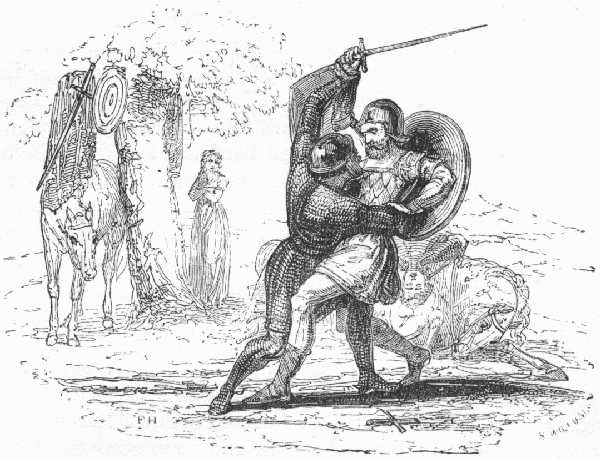

As it is our intention to arrange these traditions in chronological order, we begin with the earliest upon record, the overthrow of the giant Tarquin, near Manchester, by Sir Lancelot of the Lake, who was supposed to bear rule over the western part of Lancashire.

An old ballad commemorates the achievement; and many other relics of this tradition still exist, one of which, a rude carving on a ceiling in the College at Manchester, represents the giant Tarquin at his morning's repast; it being fabled that he devoured a child daily at this meal. The legs of the infant are seen sprawling out of his mouth in a most unseemly fashion. Some have supposed that Tarquin was but a symbol or personification of the Roman army, and his castle the Roman station in this neighbourhood.

The following extract is from Dr Hibbert's pamphlet on the subject:—

"Upon the site of Castlefield, near Manchester, was originally erected a British fortress by the Sistuntii, the earliest possessors of Lancashire, comprising an area of twelve acres. It would possess on the south, south-east, and south-west, every advantage, from the winding of the River Medlock, and on its west, from the lofty banks which overlooked an impenetrable morass. By the artificial aid, therefore, of a ditch and a rampart on its east and north sides, this place was rendered a fortress of no inconsiderable importance. This fell afterwards into the hands of the Brigantes, the ancient inhabitants of Durham, York, and Westmoreland. Upon the invasion of the Romans, Cereales, their general, attacked the proper Brigantes of Yorkshire and Durham, and freed the Sistuntii of Lancashire from their dominion, but reserved the former to incur the Roman yoke. In A.D. 79, this British hold was changed into a Roman castrum, garrisoned by the first Frisian cohort, who erected from the old materials a new fort on the Roman construction, part of the vallum remaining to this day. New roads were made, and the British were invited to form themselves into the little communities of cities, to check the spirit of independence kept alive in the uncivilised abodes of deserted forests. The Romans possessed the fortress for nearly 300 years, when they were summoned away to form part of the army intended to repel the myriads of barbarians that threatened to overrun Europe.

"By contributing to their refinement, and protecting them from the inroads of the Picts and Scots, the Romans were regarded in a friendly light by the ancient inhabitants, and their departure was much regretted. It became necessary, however, that the Britons should elect a chief from their own nation. Their military positions were strengthened; and as the Roman model of a fortress did not suit their military taste, instead of one encircled with walls only seven or eight feet high, and furnishing merely pavilions for soldiers within, they preferred erecting, on the sites of stations, large buildings of stone, whose chambers should contain more convenient barracks for the garrison. An infinite number of these castles existed within a century after the departure of the Romans, of which our Castle at Manchester was one, carried to a great height, erected in a good taste, secured at the entrances with gates, and flanked at the sides with towers.

"The Britons, however, unable of themselves to cope with their foes, imprudently invited the Saxons, who, after subduing the Caledonians, laid waste the country of the Britons with fire and sword. The Castle of Manchester surrendered A.D. 488."

We have endeavoured to preserve the character and manner of the ancient chroniclers, and even their fanciful etymologies, in the following record, of which the quaint but not inelegant style, in some measure, almost unavoidably adapts itself to the subject.

Sir Lancelot of the Lake, as it is related by the older chronicles, was the son of Ban, King of Benoit, in Brittany. Flying from his castle, then straitly besieged, the fugitive king saw it in flames, and soon after expired with grief. His queen, Helen, fruitlessly attempting to save his life, abandoned for a while her infant son Lancelot. Returning, she discovered him in the arms of the nymph Vivian, the mistress of Merlin, who on her approach sprung with the child into a deep lake and disappeared. This lake is held by some to be the lake Linius, a wide insular water near the sea-coast, in the regions of Linius or "The Lake;" now called Martin Mere or Mar-tain-moir, "a water like the sea."

The nymph educated the infant at her court, fabulously said to have been held in the subterraneous caverns of this lake, and from hence he was styled Lancelot du Lac.

At the age of eighteen the fairy conveyed him to the camp of King Arthur, who was then waging a fierce and exterminating warfare with the Saxons. Here the young warrior was invested with the badge of knighthood. His person, accomplishments, and unparalleled bravery, having won the heart of many a fair dame in this splendid abode of chivalry and romance, his name and renown filled the land, where he was throughout acknowledged as chief of "The Knights of the Round Table."

The name of Lancelot is derived from history, and is an appellation truly British, signifying royalty, Lanc being the Celtic term for a spear, and lod or lot implying a people. Hence the name of Lancelot's shire, or Lancashire. From the foregoing it is supposed that he resided in the region of Linius, and that he was the monarch of these parts, being ruler over the whole, or the greater part, of what is now called Lancashire.

Arthur, king of the Silures, being selected by Ambrosius for the command of the army, he defeated the Saxons in twelve pitched battles. Four of these were obtained, as related by Nennius, on the river called Duglas,[8] or Douglas, a little stream which runneth, as we are further told, in the region of Linius. On reference, it will be found that this river passes through a great portion of the western side of Lancashire, and pretty accurately fixes the position here described.

Three of these great victories were gotten near Wigan, and the other is currently reported to have been achieved near Black rod, close to a Roman station, then probably fortified, and remaining as a place of some strength, and in possession of the Saxon invaders. Here, according to rude legends, "the River Duglas ran with blood to Wigan three days."

It was during one of the brief intervals of rest that sometimes occurred in the prosecution of these achievements that the following incident is reported to have happened. Being a passage of some note, and the earliest tradition of the county upon record, we have chosen it as the commencement of a work principally derived from traditionary history.

Sir Tarquin, a cruel and treacherous knight of gigantic stature and prodigious strength, had, as the story is currently told, his dwelling in a well-fortified castle nigh to Manchester, on the site of what is yet known by the name of Castle-field. It was a place of great strength, surrounded by vast ramparts, and flanked at the corners with high and stately towers.

He had by treachery gained possession of the fortress, treating the owner, who was a British knight of no mean condition, with great cruelty and rigour. This doughty Saxon, Sir Tarquin, had, along with many of his nation, been invited over in aid of the Britons against their neighbours the Picts and Scots. These being driven back, their false allies treacherously made war upon their friends, laying waste the country with fire and sword. Then arose that noble brotherhood, "The Knights of the Round Table," who, having sworn to avenge the wrongs of their country, began to harass the intruders, and to drive them from their ill-gotten possessions.

The Saxons were no less vigilant; but many of their most puissant knights were slain or imprisoned during these encounters.

Sir Tarquin could boast of no mean success;—threescore knights and four, it is said, were held in thrall by this uncourteous chieftain.

Sir Lancelot having, as the ballad quaintly expresses it,

This giant knight was called Sir Carados; and Sir Lancelot, when about betaking himself to these and similar recreations, did hear doleful tidings out of Lancashire, how that Sir Tarquin was playing the eagle in the hawk's eyrie, amongst his brethren and companions. From Winchester he rode in great haste, succouring not a few distressed damsels and performing many other notable exploits by the way, "until he came to a vast desert," "frequented by none save those whom ill fortune had permitted to wander therein." Sir Tarquin, like the dragon of yore, entailed a desert round his dwelling: so fierce and rapacious was he that no man durst live beside him, save that he held his life and property of too mean account, and too worthless for the taking.

The knight was pricking on his way through this almost pathless wilderness, when he espied a damsel of such inexpressible and ravishing beauty that none might behold her without the most heart-stirring delight and admiration. To this maiden did Sir Lancelot address himself, but she hid her face and fell a-weeping. He then inquired the cause of her dolour, when she bade him flee, for his life was in great jeopardy.

"Oh, Sir Knight!" uncovering her face as she spoke, "the giant Tarquin liveth hereabout, and thou wert as good as dead should he espy thee so near his castle."

"What!" said the knight, "and shall Sir Lancelot of the Lake flee before this false and cruel tyrant? To this purpose am I come, that I may slay and make an end of him at once, and deliver the captives."

"Art thou, indeed, Sir Lancelot?" said the damsel, joy suddenly starting through her tears; "then is our deliverance nearer than we hoped for. Thy fame is gone before thee into all countries, and thy might and thy prowess, it is said, none may withstand. This evil one, Sir Tarquin, hath taken captive my true knight, who, through my cruelty, betook himself to this adventure, and now lieth in chains and foul ignominy, without hope of release, until death break off his fetters."

"Beshrew me," said Lancelot, "but I will deliver him presently, and cut off the foul tyrant's head, or lose mine own by the attempt."

Then did he follow the maiden to a river's brink, near to where, as tradition still reports, now stand the Knott Mills. Having mounted her before him on his steed, she pointed out a path over the ford, beyond which he soon espied the castle, a vast and stately building of rugged stone, like a huge crown upon the hill-top, which presented a gentle ascent from the stream.

Now did Sir Lancelot alight, as well to assist his companion as to bethink himself what course to pursue; but the damsel showed him a high tree, about a stone's-throw from the ditch before the castle, whereon hung a goodly array of accoutrements, with many fair and costly shields, on which were displayed a variety of gay and fanciful devices. These were the property of the knights then held in durance by Sir Tarquin. Below them all hung a copper basin, on which was carved in Latin the following inscription, translated thus—

This so enraged Sir Lancelot that he drove at the vessel violently with his spear, piercing it through and through, so vigorous was the assault. The clangour was loud, and anxiously did the knight await for some reply to his summons. Yet there was no answer, nor was there any stir about the walls or outworks. It seemed as though Sir Tarquin was his own castellan, skulking here alone, like the cunning spider watching for his prey.

Silence, with her vast and unmoving wings, appeared to brood over the place; and echo, that gave back their summons from the walls, seemed to labour for utterance through the void by which they were encompassed. A stillness so appalling might needs discourage the hot and fiery purpose of Sir Lancelot, who, unused but to the rude clash of arms, and the mêlée of the battle, did marvel exceedingly at this forbearance of the enemy. But he still rode round about the fortress, expecting that some one should come forth to inquire his business, and this did he, to and fro, for a long space. As he was just minded to return from so fruitless an adventure, he saw a cloud of dust at some distance, and presently he beheld a knight galloping furiously towards him. Coming nigh, Sir Lancelot was aware that a captive knight lay before him, bound hand and foot, bleeding and sore wounded.

"Villain!" cried Sir Lancelot, "and unworthy the name of a true and loyal knight, how darest thou do this insult and contumely to an enemy, who, though fallen, is yet thine equal? I will make thee rue this foul despite, and avenge the wrongs of my brethren of the Round Table."

"If thou be for so brave a meal," said Tarquin, "thou shalt have thy fill, and that speedily. I will first cut off thy head, and then serve up thy carcase to the Round Table; for both that and thee I do utterly defy!"

"This is over-dainty food for thy sending," replied Sir Lancelot hastily, and with that they couched their spears. The first rush was over, but man and horse had withstood the shock. Again they fell back, measuring the distance with an eager and impetuous glance, and again they rushed on, as if to overwhelm each other by main strength, when, as fortune would have it, their lances shivered, both of them at once, in the rebound. The end of Sir Lancelot's spear, as it broke, struck his adversary's steed on the shoulder, and caused him to fall suddenly, as if sore wounded. Sir Tarquin leaped nimbly from off his back; which Sir Lancelot espying, he cried out—

"Now will I show thee the like courtesy; for, by mine honour and the faith of a true knight, I will not slay thee at this foul advantage." Alighting with haste, they betook themselves to their swords, each guarding the opposite attack warily with his shield. That of Sir Tarquin was framed of a bull's hide, stoutly held together with thongs, and, in truth, seemed well-nigh impenetrable; whilst the shield of his opponent, being of more brittle stuff, did seem as though it would have cloven asunder with the desperate strokes of Sir Tarquin's sword. Nothing daunted, Sir Lancelot brake ofttimes through his adversary's guard, and smote him once until the blood trickled down amain. At this sight, Sir Tarquin waxed ten times more fierce; and summoning all his strength for the blow, wrought so lustily on the head of Sir Lancelot that he began to reel; which Tarquin observing, by a side blow struck the sword from out his hand, with so sharp and dexterous a jerk that it shivered into a thousand fragments.

"Now yield thee, Sir Knight, or thou diest;" and with that the cruel monster sprang upon him to accomplish his end. Still Sir Lancelot would not yield, nor sue to him for quarter, but flew on his enemy like the ravening wolf to his prey. Then were they seen hurtling together like wild bulls—Sir Lancelot holding fast his adversary's sword, so that in vain he attempted to make a thrust therewith.

"Thou discourteous churl! give me but the vantage of a weapon like thine own, and I will fight thee honestly and without flinching."

"Nay, Sir Knight of the Round Table, but this were a merry deed withal, to help thee unto that wherewith I might perchance mount some goodly bough for the crows to peck at," replied Tarquin. Terrible and unceasing was the struggle; but in vain the giant knight attempted to regain the use of his sword. Then Sir Lancelot, with a wary eye, finding no hope of his life save in the use or accomplishment of some notable stratagem, bethought him of the attempt to throw his adversary by a sudden feint. To this end he pressed against him heavily and with his whole might, then darting suddenly aside, Sir Tarquin fell to the ground with a loud cry; which Sir Lancelot espying, leapt joyfully upon him, thinking to overcome his enemy; but the latter, too cunning to be thus caught at unawares, kept his sword firmly holden, and his enemy was still unprovided with the means of defence. Now did Sir Lancelot begin to doubt what course he should pursue, when suddenly the damsel, who, having bound up the wounds of the captive knight as he lay, and now sat a little way off watching the event, cried out with a shrill voice—

"Sir Knight, the tree:—a goodly bough for the gathering." Then did Sir Lancelot remember the weapons that were there, along with the shields and the body-armour of the knights Sir Tarquin had vanquished. Starting up, ere his enemy had recovered himself, he snatched a broad falchion from the bough, and again defied him to the combat. But the fight was fiercer than before; so that being sore wounded, and the day exceeding hot, they were after a season fain to pause for breath.

"Thou art the bravest knight I ever encountered," said Sir Tarquin, "and I would crave thy country and thy name; for, by my troth and the honour of my gods, I will give thee thy request on one condition, and release thy brethren of the Round Table; for why should two knights of such pith and prowess slay each other in one day?"

"And what is thy condition?" inquired Sir Lancelot.

"There liveth but one, either in Christendom or Heathenesse, unto whom I may not grant this parley; for him have I sworn to kill," said Sir Tarquin.

"'Tis well," replied the other; "but what name or cognisance hath he?"

"His name is Lancelot of the Lake!"

"Behold him!" was the reply; Sir Lancelot at the same time brandishing his weapon with a shout of defiance.

When Sir Tarquin heard this he gnashed his teeth for very rage.

"Now one of us must die," said he. "Thou slewest my brother Sir Carados at Shrewsbury, and I have sworn to avenge his defeat. Thou diest. Not all the gods of thy fathers shall deliver thee."

So to it they went with more heat and fury than ever; and a marvel was it to behold, for each blow did seem as it would have cleft the other in twain, so deadly was the strife and hatred between them.

Sir Lancelot pressed hard upon his foe, though himself grievously wounded, and in all likelihood would have won the fight, but, as ill-luck would have it, when dealing a blow mighty enough to fell the stoutest oak in Christendom, he missed his aim, and with that stumbled to the ground. Then did Sir Tarquin shout for joy, and would have made an end of him, but that Sir Lancelot, as he lay, aimed a deadly thrust below his enemy's shield where he was left unguarded, and quickly turned his joy into tribulation; for Sir Tarquin, though not mortally wounded, drew back and cried out lustily for pain, the which Sir Lancelot hearing, he leapt again to his feet, still eager and impatient for the strife.

The contest was again doubtful, neither of them showing any disposition to yield, or in any wise to abate the rigour of the conflict. Night, too, was coming on apace, and seemed like enough to pitch her tent over them, ere the issue was decided. But an event now fell out which, unexpectedly enough, terminated this adventure. From some cause arising out of the haste and rapidity of the strokes, one of these so chanced, that both their swords were suddenly driven from out of their right hands; stooping together, by some subtlety or mistake, they exchanged weapons. Then did Sir Lancelot soon find his strength to increase, whilst his adversary's vigour began to abate; and in the end Sir Lancelot slew him, and with his own sword cut off his head. He then perceived that the giant's great strength was by virtue of his sword; and that it was through his wicked enchantments therewith he had been able to overcome, and had wrought such disgrace on the Knights of the Round Table. Sir Lancelot forthwith took the keys from the giant's girdle, and proceeded to the release of the captive knights, first unbinding the prisoner, who yet lay in a piteous swoon hard by. But there was a great outcry and lamentation when that he saw his own brother Sir Erclos in this doleful case; for it was he whom the cruel Tarquin was leading captive when he met the just reward of his misdeeds.

After administering to his relief, Sir Lancelot rode up to the castle-gate, but found no entrance thereby. The drawbridge was raised, and he sought in vain the means of giving the appointed signal for its descent.

But the damsel showed him a secret place where hung a little horn. On this he blew a sharp and ringing blast, when the bridge presently began to lower, and instantly to adjust itself across the moat; whereon, hastening, he unlocked the gate. But here he had nigh fallen into a subtle snare, by reason of an ugly dwarf that was concealed in a side niche of the wall. He was armed with a ponderous mace; and had not the maiden drawn Sir Lancelot aside by main force, he would have been crushed in its descent, the dwarf aiming a deadly blow at him as he passed. It fell, instead, with a loud crash on the pavement, and broke into a thousand fragments. Thereupon, Sir Lancelot smote him with the giant's sword, and hewed the mischievous monster asunder without mercy. Turning towards the damsel, he beheld her form suddenly change, and she vanished from his sight: then was he aware that it had been the nymph Vivian who accompanied him through the enchantments he had so happily subdued. He soon released his brethren, and great was the joy at the Round Table when the Knights returned to the banquet.

Thus endeth the chronicle of Sir Tarquin, still a notable tradition in these parts, the remains of his castle being shown to this day.

[8] Du-glass, "the becoming, the seemly, green," described by Camden as "a small brook, running with an easy and still stream;" which conveys a good idea of the word Du. The Du-glass empties itself into the estuary called by Ptolemy Bellesama, Belless-aman-e; pronounced Violish-anne,[9] the literal meaning of which is, that the "mouth of the river only is for ships;" i.e., that the rivers which form the haven are not navigable.—Chronicles of Eri.—O'Connor.

[9] Ballyshannon is evidently a very slight corruption of this term.

The story which serves for the basis of the following legend will be easily recognised in the neighbourhood where the transactions are said to have occurred, though probably not known beyond its immediate locality.

The accessories are gathered from a number of sources: and the great difficulty the author has had to encounter in getting at what he conceives the real state and character of the time, together with the history of contemporary individuals and events, so as to give a natural picture of the manners and customs of that remote era, can be known by those only who have entered into pursuits of this nature. In this and in the succeeding legends he has attempted to illustrate and portray the customs of that particular epoch to which they relate, as well as to detail the events on which they are founded.

It may be interesting to notice that a similar exploit is recorded in the Scandinavian Legends, and may be traced, under many variations of circumstances and events, in the Icelandic, Danish, and Norwegian poetry, affording another intimation of the source from whence our popular mythology is derived.

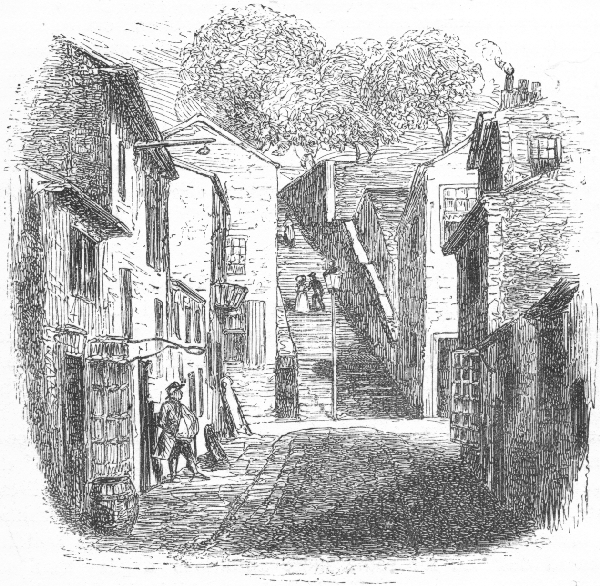

Towards the latter end of the reign of William, the Norman conqueror, Gamel, the Saxon Thane, Lord of Recedham or "Rached," being left in the quiet possession of his lands and privileges by the usurper, "minded," as the phrase then was, "for the fear of God and the salvation of his immortal soul, to build a chapel unto St Chadde," nigh to the banks of the Rache or Roach. For this pious use a convenient place was set apart, lying on the north bank of the river, in a low and sheltered spot now called "The Newgate." Piles of timber and huge stones were gathered thither in the most unwonted profusion; insomuch, that the building seemed destined for some more ambitious display than the humble edifices called churches then exhibited, of which but few existed in the surrounding districts.

The foundations were laid. The loose and spongy nature of the soil required heavy stakes to be driven, upon and between which were laid several courses of rubble-stone, ready to receive the grouting or cement. Yet in one night was the whole mass conveyed, without the loss of a single stone, to the summit of a steep hill on the opposite bank, and apparently without any visible marks or signs betokening the agents or means employed for its removal. It did seem as though their pathway had been the viewless air, so silently was all track obliterated. Great was the consternation that spread among the indwellers of the four several clusters of cabins dignified by the appellation of villages, and bearing, with their appendages, the names of Castletown, Spoddenland, Honorsfield, and Buckland. With dismay and horror this profanation was witnessed. The lord, more especially, became indignant. This daring presumption—this wilful outrage, so like bidding defiance to his power, bearding the lion even in his den, was deemed an offence calling for signal vengeance upon the perpetrators.

At the cross in Honorsfield a proclamation was recited, to the intent, that unless the offending parties were forthwith given up to meet the punishment that might be awarded to their misdeeds, a heavy mulct would follow, and the unfortunate villains and bordarii be subject to such further infliction as might still seem wanting to assuage their lord's displeasure. Now this was a grievous disaster to the unhappy vassals, seeing that none could safely or truly accuse his neighbour. All were agreed that human agency had no share in the work. The wiser part threw out a shrewd suspicion, that the old deities whom their forefathers had worshipped, and whose altars had been thrown down and their sacrifices forbidden, had burst the thraldom in which they were aforetime held by the Christian priests, and were now brooding a fearful revenge for the many insults they had endured. But the decree from the lord was hasty, and the command urgent; so that a council was holden for the devising of some plan for their relief.