The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Tale of Peter Mink, by Arthur Scott Bailey

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Tale of Peter Mink

Sleepy-Time Tales

Author: Arthur Scott Bailey

Illustrator: Joseph Guzie

Release Date: June 16, 2007 [EBook #21845]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE TALE OF PETER MINK ***

Produced by Joe Longo and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

|

|

|

BY

ARTHUR SCOTT BAILEY

AUTHOR OF

THE CUFFY BEAR STORIES

SLEEPY-TIME TALES, ETC.

Illustrations by

Joseph B. Guzie

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS NEW YORK

|

Copyright, 1916, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | |

PAGE |

| I | How Peter Was Different | 9 |

| II | Sawing Wood | 13 |

| III | Making Peter Work | 19 |

| IV | The Lecture | 25 |

| V | Passing the Hat | 31 |

| VI | Mr. Rabbit Is Worried | 38 |

| VII | Peter's Bad Temper | 43 |

| VIII | At the Garden-Party | 48 |

| IX | Helping Jimmy Rabbit | 53 |

| X | What Could Peter Do? | 59 |

| XI | The Circus Parade | 64 |

| XII | Peter Learns a New Word | 69 |

| XIII | Good News About Peter | 75 |

| XIV | Uncle Jerry Helps | 80 |

| XV | Peter's New Coat | 85 |

| XVI | The Duck Pond | 90 |

| XVII | How To Be Lucky | 96 |

| XVIII | The Bargain | 101 |

| XIX | Settling a Dispute | 107 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

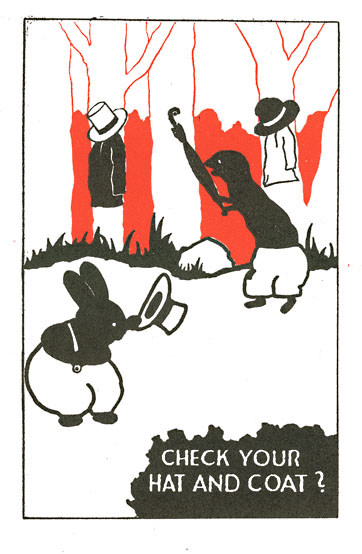

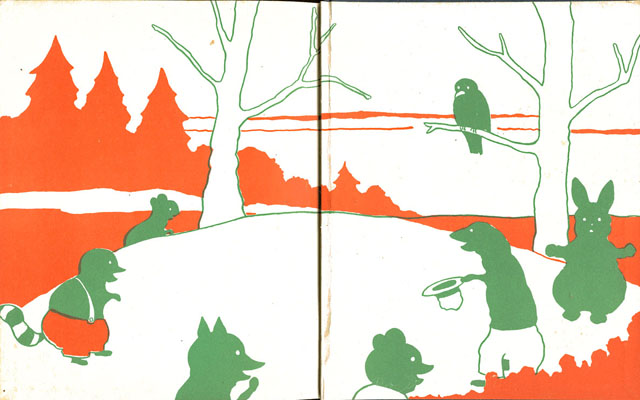

| CHECK YOUR HAT AND COAT? |

Frontispiece |

| PETER SPLIT THE STICK PERFECTLY! | 22 |

| JIMMY WENT SAILING THROUGH THE AIR | 62 |

| PETER PULLED JIMMY OUT OF THE MUD | 90 |

p. 9

There were two ways in which Peter

Mink was different from any other person

in Pleasant Valley, or on Blue Mountain,

either. In the first place, he had no home;

and in the second, he had a very long neck.

The reason why Peter had no home was

because he didn't want one. And the reason

why he had such a long neck was because

he couldn't help it.

When he grew sleepy he would crawl

p. 10into any snug place he happened to find—sometimes

in a hollow stump, or in a pile

of rocks, or a haystack. And often he

even drove a muskrat out of his house, so

he could sleep there.

Most of the time Peter Mink went about

in rags and tatters. Whenever he did

have a new suit (which wasn't often) it

never looked well for long. Naturally,

sleeping in all sorts of places did not improve

it. But what specially wore out his

clothes was the way he was always squeezing

through small holes and cracks.

Wherever Peter saw a narrow place he

never could resist trying to get through it.

He was a long, slim fellow, with a small,

snake-like head. And he always knew that

if he could squeeze his head through a

crack he could get his body through it, too.

It is not at all strange that Mrs. Rabbit

and Mrs. Squirrel and Mrs. Woodchuck—as

well as a good many other people—didp. 11

not care to have their sons in Peter Mink's

company. They said that any one who

went about looking as untidy as he did,

and without a home, was not likely to set

a good example to the young.

But Jimmy Rabbit and Frisky Squirrel

and Billy Woodchuck loved to be with

Peter Mink. To be sure, he was quarrelsome.

And he was always ready to fight

any one four times as big as he was. So

they had to be careful not to offend him.

But in spite of that, they found him interesting—he

was such a fine swimmer. He

could swim under water just as well as he

could swim with his head above the surface.

And in winter he was not afraid to

swim under the ice in Broad Brook.

There was another thing about Peter

Mink that made the younger forest people

admire him. He was a famous fisherman.

He could dive for a trout and catch himp. 12

too, just as likely as not. And there was

nothing more exciting than to see Peter

Mink pull an eel out of the water.

It is really a great pity that he was so

rough. But you see, he left home at an

early age and grew up without having any

one to tell him what he ought—and ought

not—to do. No doubt he didn't know the

difference between right and wrong. Jimmy

Rabbit's mother used to call him "the

Pest." She often remarked that she

wished Peter would leave the neighborhood

and never come back.

I am sure that Johnnie Green's father

would have agreed with her, because

Peter Mink was too fond of ducks to suit

Farmer Green. Of course, Peter didn't

care to eat ducks all the time. Sometimes

he dined on a fat hen. But even then

Farmer Green was angry. No doubt

Peter Mink thought him hard to please.

p. 13

It was really no wonder that Mrs. Rabbit

did not like Peter Mink. When you hear

what happened the very first time she saw

him you will understand why Mrs. Rabbit

always called him "the Pest."

One day Mrs. Rabbit heard a knock on

her door. And when she went to see who

was there, she found a ragged young fellow,

with his hat tipped far over on one

side. Instead of a collar, he wore a handkerchief

about his neck. But it would

have taken at least a dozen handkerchiefs,

tied one above another, to cover

the stranger's neck; for it was by far thep. 14

longest neck Mrs. Rabbit had ever seen.

"What do you want?" Mrs. Rabbit

asked.

"Something to eat!" said the stranger.

You notice that he didn't say "Please!"

That was a word that Peter Mink had

never used. Probably he didn't even know

what it meant.

Now, Mrs. Rabbit saw that the stranger

was very thin. She did not know that no

matter how much he ate, he would never

be what you might call fat. That slimness

was something that ran in Peter Mink's

family. The Minks were always slender

people.

Being a kind-hearted soul, Mrs. Rabbit

went back to her kitchen. And soon

she brought Peter a plateful of the best

food she had.

"You're not ill, are you?" she asked

Peter.

p. 15

"No!" he answered, as he took the dish.

"Then," said Mrs. Rabbit, "I shall expect

you to do some work, to pay for this

food."

"All right!" said Peter. But he wished

that he had said he was ill. For he simply

hated work. And he made it a rule never

to do a stroke of work if he could avoid it.

Well, he sat down on Mrs. Rabbit's

doorstep and ate what she had given him.

And while he was eating, Jimmy Rabbit

came out and watched him. Even Jimmy

Rabbit could see that he had very bad

manners. He held something to eat in each

hand. And he didn't seem to care from

which hand he ate, so long as he kept his

mouth stuffed so full that he could hardly

talk.

"What's your name?" Peter Mink

asked Jimmy. And when Jimmy told him,

he said: "No wonder you're fat, with suchp. 16

good things to eat as your mother makes."

When Mrs. Rabbit heard that she was

pleased. And for a time she thought that

perhaps the stranger was not so bad as he

looked.

When he had almost finished his lunch,

Mrs. Rabbit went back into her house once

more. And pretty soon she came out with

a saw in her hand. She gave the saw to

Peter Mink and said:

"Now you may saw some wood, to pay

me for the food. You'll find the wood-pile

behind the house. And you may saw all of

it," she added.

Peter Mink took the saw and started for

the wood-pile. And Jimmy Rabbit followed

him. Peter sawed just one stick of

wood; and then he said to Jimmy:

"Go in and ask your mother if she can't

find an old pair of shoes for me."

So Jimmy ran into the house to find hisp. 17

mother. And kind-hearted Mrs. Rabbit

began at once to hunt for a pair of shoes

to give the stranger. She had noticed that

his toes were sticking out.

Pretty soon she found some shoes which

she thought would fit the stranger. And

when she stepped to her door again, there

he was, waiting for her.

"What! Is the wood all sawed so

soon?" asked Mrs. Rabbit. "If it is,

you're a spry worker, young man!"

"The saw—" said Peter Mink—"the

saw is no good at all. It broke before I

finished sawing half the wood-pile." And

that was true, too, in a way; because he

had only sawed one stick.

"Well, if you've finished half of it you

haven't done badly," Mrs. Rabbit told

him. And she gave Peter Mink the shoes.

"They're not very new," he grumbled.

"But they're better than none."

p. 18

They certainly were much better than

the shoes he had been wearing.

Then Peter Mink went slouching off.

He did not even thank Mrs. Rabbit for her

kindness. He did not even take away his

old shoes, but left them on the doorstep

for Mrs. Rabbit to pick up.

"I must say that young man has had no

bringing up at all," she told Jimmy. "I

hope this is the last we'll see of him....

Come!" she said. "Help me bring in some

of the wood he sawed."

Well, Mrs. Rabbit was surprised when

she found that the stranger had sawed

only one stick.

When Mr. Rabbit came home he took

just one look at his broken saw. And he

was more than surprised. He was angry.

"Why," he said, "I do believe that

good-for-nothing rascal broke my saw on

purpose, so he wouldn't have to work."

p. 19

Peter Mink waited several days before

he knocked at Mrs. Rabbit's door again.

And when he did at last come back, he first

made sure that her husband was not at

home. You see, Peter had heard that Mr.

Rabbit had told some of the forest-people

that Peter had broken his saw, so he

wouldn't have to saw wood to pay for the

food that Mrs. Rabbit gave him.

When Mrs. Rabbit saw who it was that

knocked, she came very near shutting the

door in Peter's face. But she couldn't

help noticing again how thin Peter was.

And when he asked again for something top. 20

eat she hadn't the heart to refuse him.

"You're not ill, are you?" she asked.

"Well—yes, I am!" said Peter Mink,

boldly. He would actually rather tell a lie

than work. And he thought that if he said

he was ill, Mrs. Rabbit wouldn't expect

him to do any work to pay for what she

might give him.

"You look to me as if you needed some

cambric tea," Mrs. Rabbit said.

Now, if there was anything that Peter

Mink disliked, it was cambric tea. If she

had said "chicken broth," he might have

liked that.

"I've been very ill," he said. "But now

the doctor tells me I must have good, nourishing

food—and plenty of it."

"Well, if you're well enough to eat,

you're well enough to work," said Mrs.

Rabbit.

"Oh, certainly!" answered Peter.

p. 21

Mrs. Rabbit went into the house then.

And when she came out again Peter Mink

was surprised at what she brought. He

had expected another plateful of goodies.

But instead of that, Mrs. Rabbit had an

axe in her hand.

"Here!" she said. "Take this out to the

wood-pile—and use it! I want you to split

every stick of wood you can find. Then

knock on the door again and I'll bring you

something to eat."

You ought to have seen Peter Mink

scowl, as he walked away to the wood-pile

with the axe on his shoulder. It was a lesson

to anybody, never to frown!

"She needn't think she can make me

work!" Peter said to himself. "I'll just

break her old axe—that's what I'll do!"

And he swung the axe with all his might

at a stick of wood.

But the axe didn't break. And as forp. 22

the stick, it fell in two pieces; for Peter

had split it perfectly.

He was so out of patience that he aimed

a hard blow at another stick of wood.

Again, he didn't hurt the axe at all. And

again he split the wood exactly as Mrs.

Rabbit wanted him to. But Peter never

thought of that.

Peter Mink scowled even worse than

ever. And he made up his mind that he

would break Mrs. Rabbit's axe if he had

to use up the whole wood-pile to do it.

Well, that is just what happened. Peter

tried so hard to break the axe so he

wouldn't have to work, that before he

knew it he had split all the wood.

He was just about to look for a rock,

then—on which to break the axe—when

he happened to think that there was no

longer any sense in trying to do that, because

the work was all done!

p. 23

So he put the axe across his shoulder

and went and knocked on Mrs. Rabbit's

door.

"Bring on your food!" he said, when

Mrs. Rabbit appeared.

"Is the axe all right?" she asked. "It

didn't break, did it?"

"No, indeed!" he said—"though I

was rather expecting it would."

"Is the wood all split?" she inquired.

"Every stick of it!" answered Peter.

"Then bring it here, near the back

door," Mrs. Rabbit told him. "That will

help pay for the saw you broke here last

week."

"I'll do nothing of the kind!" said

Peter Mink. And he was so angry that

he went back to the wood-pile and began

throwing sticks of wood at Mrs. Rabbit's

house, trying to break a window. And

before he knew it he had thrown the wholep. 24

wood-pile in almost the exact spot where

Mrs. Rabbit wanted it. And he hadn't

broken a single window, either.

But Peter Mink never once realized

what he had done. He went off to take a

swim in the brook, and maybe catch a

trout.

Later when Mrs. Rabbit saw that in

spite of what Peter had said, he had

moved her wood-pile for her, she wondered

why he had not asked for something to

eat. But Peter Mink never knocked on

her door again. He kept away from Mrs.

Rabbit ever afterward, because she was

the only person who had ever been able to

make him work.

p. 25

Peter Mink was going to give a lecture.

He had invited everybody.

"It's something you all ought to hear,"

he said. "And it will cost you nothing to

come. Another time," he explained,

"whoever hears my lecture will have to

pay. But this one is free."

Old Mr. Crow remarked that he supposed

Peter Mink was going to tell people

how to catch ducks. And since he never

cared anything at all about ducks, he said

he didn't expect to be present.

"I'm glad you're not coming," Peter

Mink answered, "because I'm afraid therep. 26

won't be room for all the people who intend

to hear me. As for ducks—I'd no

more think of giving a lecture about ducks

than I would about crows."

Old Mr. Crow pretended not to hear

what Peter said. He did not care even to

be seen talking with such a worthless fellow.

But there were many other people living

in Pleasant Valley and on Blue Mountain

who decided to go to Peter Mink's lecture—when

they learned that they might get

in free.

And when the night of the lecture arrived

even Peter himself was surprised to

see how many were present.

To be sure, Peter noticed that some of

the audience were smiling; and some of

them were nudging one another, as if they

thought the whole thing was nothing but

a joke. And when the full moon climbedp. 27

over the top of Blue Mountain, and Peter

Mink climbed on top of an old stump and

faced the gathering, a few rude persons

laughed aloud.

"What about ducks?" somebody called

from a tree above Peter's head. Everybody

tittered at that, because everybody

knew that Peter was very fond of ducks

and spent much of his time at Farmer

Green's duck pond.

It was old Mr. Crow who asked that

question. He had come to the lecture, in

spite of what he had said.

"My lecture," Peter Mink began, when

all was quiet, "my lecture to-night is going

to be about a poor boy who has no one

to take care of him. He has no home.

And very often he goes about in rags.

Sometimes he begs for food and clothes.

I think," Peter said, "we all ought to be

very sorry for him."

p. 28

As soon as Peter said that, Mrs. Squirrel

and Mrs. Woodchuck took out their

pocket-handkerchiefs and wiped their

eyes. And Mrs. Squirrel's husband was

heard to remark that it was a shame, and

that he thought something ought to be

done.

Well, Peter Mink went on and told them

as many as twenty-three different tales

about that poor boy, to show them what a

hard life he led. Every tale was sadder

than the one just before it. And by the

time Peter had finished the twenty-third,

there were very few dry eyes in the place.

And Mr. Squirrel spoke up loudly and

said once more that something ought to be

done about it.

When he said that, Uncle Jerry Chuck

rose hurriedly and hobbled away from the

lecture. He had sat in one of the best

seats, because it was free. And he hadp. 29

wept quite noisily, once or twice, because

it cost no more to weep and he wanted all

he could get for nothing. But when Mr.

Squirrel said what he did, Uncle Jerry at

once thought of a collection. And he decided

that he had better leave before it was

too late.

Peter Mink saw him go. And here and

there he noticed other people who looked

as if they would like to leave, too. And he

knew that there was no time to lose.

"I see one gentleman leaving," Peter

Mink said in a loud voice. "I hope no

more will go—unless, of course, they're so

stingy that they wouldn't care to give a

little something to help this poor boy I've

been telling you about."

After that, nobody wanted to leave, because

nobody wanted to be thought stingy.

"I appoint Mr. Rabbit and Mr. Woodchuck

to take up a collection for this poorp. 30

boy," Peter Mink said. "And I've no

doubt that they will be glad to give all they

can, themselves."

Mr. Rabbit and Mr. Woodchuck saw

that everybody was looking at them. And

they at once emptied their pocket-books

into their hats.

"What's his name? What's the poor

boy's name?" a hoarse voice called. It

was Mr. Crow who asked the question.

"That," said Peter Mink, "is something

I do not care to tell to everybody."

And many people clapped their hands.

They were beginning to have a better opinion

of Peter Mink.

But old Mr. Crow only laughed loudly

from his perch in the tree.

p. 31

After giving all they happened to have in

their pocket-books, Mr. Rabbit and Mr.

Woodchuck began to pass their hats to

take up the collection for the poor boy that

Peter Mink had been telling them about.

And all the people who had come to hear

Peter's lecture began to dig down into

their pockets.

"That's right!" Peter cried. "Give

what you can! Of course, I don't expect

the poor people to give as much as the

rich."

That made everybody decide that he

would give all he had with him. And manyp. 32

people wished they had brought more. Besides,

no one wanted to be thought stingy,

like Uncle Jerry Chuck, who had hurried

away as soon as he suspected that there

was going to be a collection.

When Mr. Rabbit and Mr. Woodchuck

had passed their hats to every person present,

their hats were filled to the brim. And

they marched proudly up to the stump

where Peter Mink still stood.

Peter jumped down to the ground.

"Keep your seats, everybody!" he

called. "The next thing to be done is to

count this money. And I will do that myself."

So Peter picked up the two hats

and started away.

"Where are you going?" Mr. Rabbit

asked him.

"Just a little way into the woods," said

Peter. "It's so noisy here, with all this

talking, that I might make a mistake."

p. 33

"We'll go with you and help you," Mr.

Rabbit told him.

"Oh, you don't need to do that," said

Peter Mink.

But Mr. Rabbit insisted.

"One of those hats is mine," he remarked.

"And wherever it goes, I go,

too," And he beckoned to Mr. Woodchuck

to follow.

Well, Peter Mink didn't like that very

well. You see, he had planned to go into

the woods alone with the money. And nobody

likes to have his plans upset. But

there was nothing he could say. So they

all three went into a thicket of elderberry

bushes and counted the money.

"I thought there was more," Peter said.

"Maybe we dropped some of the money.

You and Mr. Woodchuck had better go

back and see if you can find any," he told

Mr. Rabbit.

p. 34

But Mr. Rabbit said that they could just

as well all go back together and search

along the ground as they went.

"All right!" said Peter Mink. "Well

leave these hatfuls right here for a while."

But Mr. Rabbit said he didn't think that

would be a safe thing to do. So he picked

up one hatful, and told Mr. Woodchuck

to carry the other.

Peter Mink didn't like that at all. But

there was nothing he could say. So they

all went back together to the place where

the rest of the people were still waiting.

And they found no more money, either.

Mr. Rabbit jumped up on the stump

where Peter had stood and talked.

"The question is," he said, "who is going

to take charge of all this money?"

"I am!" said Peter Mink.

But Mr. Rabbit said he didn't think that

would be safe.

p. 35

"You have no home, you know," he told

Peter. "And you can't very well carry

the money about with you. I must have

my hat back; and no doubt Mr. Woodchuck

will want his, too."

Mr. Woodchuck nodded his head. He

certainly did want his hat. It was the best

one he had.

"I would suggest—" said Mr. Rabbit

then—"I would suggest that I take one

hatful home with me, and that Mr. Woodchuck

take the other to his house. Then

we'll each have our hats; and the money

will be perfectly safe."

"That's a good idea!" Peter Mink said.

"The only trouble with it is that it won't

do at all. For you and Mr. Woodchuck

don't know the poor boy. So how could

you ever give him the money?"

Everybody said that was so.

"This Peter Mink is certainly a brightp. 36

young fellow," people told one another.

Mr. Rabbit looked puzzled.

"What do you suggest, then?" he asked

Peter.

Peter Mink smiled. He seemed pleased,

for one reason or another.

"This stump," he said, "is hollow. As

you can all see, there's a small hole in it.

We can put the money in there and nobody

can get it out. It will be the same as

in a bank."

Mr. Rabbit looked at the hole in the

stump.

"I know I can't get through that hole,"

he said. "But what about you, young fellow?"

he asked Peter.

"Oh, I can't squeeze through such a

small hole as this," said Peter. "See!"

He pushed his nose part way through the

hole. And there his head seemed to stick.

He could have squirmed through if he hadp. 37

really tried. But nobody else seemed to

know it.

"But how is the poor boy ever going to

get his money?" Mr. Rabbit inquired.

"Oh, he's very slim," Peter Mink said.

"He can get inside the stump. Don't you

worry about him!"

Everybody seemed satisfied. So they

dropped the money through the hole.

And then Mr. Rabbit said:

"When are you going to bring the poor

boy to get the money?"

"To-morrow night would be a good

time," Peter Mink said. "Would you all

like to come here to-morrow night at this

same hour?"

And everybody said, "Yes!"

p. 38

When Mr. Rabbit reached home, after

Peter Mink's lecture, and told his wife

about the money that had been collected

for the poor boy whom Peter Mink knew,

she asked:

"Who has the money?"

"Oh, it's safe," said Mr. Rabbit. "It's

hidden in an old stump. And the hole in

the stump is so small that even Peter himself

can't crawl through it."

"How do you know he can't?"

"He tried," said Mr. Rabbit.

"How do you know he tried as hard as

he could?" Mrs. Rabbit asked.

p. 39

That was what made Mr. Rabbit worry.

So instead of going to bed, he hurried back

to the place where Peter had given his famous

lecture; and there he hid himself

under a small pine.

Mr. Rabbit hadn't waited long before

he saw some one come out of the elderberry

bushes and hurry up to the stump.

It was Peter Mink! He had a bag in his

hand. And while Mr. Rabbit was watching,

he squeezed through the hole in the

stump. Even for Peter Mink the hole was

almost too small. But he managed to

squirm through, though it cost him a few

groans; and he said some words that made

Mr. Rabbit shake his head.

Well, as soon as Peter was inside the

hole he began to push the money through

it. And then what do you suppose Mr.

Rabbit did? He crept up to the stump,

picked up the bag, which Peter had leftp. 40

on the ground, and as fast as the money

rolled out of the hole, Mr. Rabbit put it

inside the bag.

The bag was almost full when the money

stopped rolling out of the hole. And Mr.

Rabbit heard Peter Mink say to himself:

"That seems to be all!"

And as soon as he heard that, Mr. Rabbit

hurried away, with the bag of money

over his shoulder.

Peter Mink waited a bit, to see if he

could find more money. But he had

thrown it all out. So he squeezed through

the hole again. Then he turned to pick

up the bag. But it had vanished.

"That's queer!" said Peter Mink. "I

thought I left that bag right here." He

looked all around, but he couldn't find it

anywhere. So he took off his ragged

coat and laid it on the ground. "I'll put

the money in this!" Peter said.

p. 41

But when he looked for the money he

couldn't find a single piece.

"That's queer!" said Peter. "It must

have rolled away from the stump." And

he began to search all about. But the

money, too, had vanished completely. And

Peter Mink couldn't understand it.

The following night, when everybody

came back again, expecting that Peter

Mink would bring the poor boy with him

to get the money, Peter never appeared

at all.

Finally Mr. Rabbit jumped on top of

the stump and told his friends what had

happened the night before.

"And now," he said, "everybody can

come right up here and get his money

back, for there's no doubt at all that Peter

Mink was collecting it for himself. He

was the poor boy he told us about."

Everybody was surprised. But everybodyp. 42

was glad to get his money again. In

fact, there was only one person who

grumbled; and that was Uncle Jerry

Chuck. He hurried up to the stump ahead

of all the rest, to get some money. And

he seemed more surprised than ever when

Mr. Rabbit said there was no money there

for him.

"I was at the lecture last night," Uncle

Jerry said.

"But you left before the money was

collected," Mr. Rabbit replied.

Uncle Jerry admitted that that was so.

But he claimed that he had made less

trouble for everybody, because no one had

been obliged to handle the money that he

hadn't given.

But Mr. Rabbit told him he ought to be

ashamed of himself. And every one will

say that Peter Mink ought to have been

ashamed of himself, too.

p. 43

Peter Mink was always quarreling. And

he seemed always ready to fight—to fight

even people who were four times bigger

than he was. And when he fought, Peter

usually won. But there was one person

Peter Mink was afraid of; and that was

Fatty Coon. Fatty was almost too big for

Peter Mink to whip. And his teeth were

very sharp. And his claws were like

thorns.

One day Peter and Fatty had a dispute.

Fatty Coon had said that a hen made the

finest meal in the world. But Peter Mink

spoke up at once and said it wasn't so.

p. 44

"There's nothing quite like a duck," he

said.

Fatty Coon sneered.

"Ducks may be all right," he cried. "In

fact, in my opinion they are far too good

for any member of the Mink family to eat.

But for me—give me a plump hen!" And

just thinking about hens made him

hungry. And being hungry made him

think of green corn. "Give me a plump

hen and plenty of green corn!" And he

looked all around, as if he expected somebody

would hurry up to him with a hen in

one hand and a dozen ears of corn in the

other.

But nobody came.

"You're a big glutton!" Peter Mink

shouted. He was very angry. But he did

not dare fight Fatty Coon.

"I guess you wish I was smaller," said

Fatty Coon, "so you could fight me."

p. 45

At that, Peter Mink looked very fierce.

And he turned to Frisky Squirrel and

Billy Woodchuck and Jimmy Rabbit and

shouted:

"Take hold of me, quick, you fellows—before

I hurt him! For I can't keep my

hands off him a second longer!"

When they heard that, Fatty's friends

were frightened. They were afraid Peter

Mink would fly at him and hurt him terribly.

So they all seized Peter and held

him fast, while they begged Fatty to run

away.

Now, Fatty Coon was not the least bit

afraid of Peter. But talking of good

things to eat had made him so hungry that

he felt he must hurry down to Farmer

Green's cornfield at once. So he said

"Good-bye!" and left them.

After Fatty had disappeared, Peter

Mink said it was safe to let him go again,p. 46

but that it was lucky they had held him.

And Frisky Squirrel and Billy Woodchuck

and Jimmy Rabbit agreed afterwards

that Peter Mink was a dangerous

fellow. They were glad that Fatty Coon

had escaped.

The next day, almost the same thing

happened again. Only this time Peter

Mink remarked that there was nothing

any tastier than a fine eel. Fatty Coon

told him that eels might be good enough

for the Mink family, but as for him, he

preferred green peas.

"Somebody hold me, quick!" Peter

Mink screamed. "I don't want to hurt

him—but I'm losing my temper fast."

Several of Fatty Coon's friends started

to seize Peter Mink, so Fatty might run

away. But there was one person present

who had not been there the day before.

This was Tommy Fox. And he onlyp. 47

laughed when Peter Mink said what he

did.

"Don't touch him!" Tommy Fox told

the others. "Let's see what he'll do.

Fatty isn't afraid of him."

"Why, certainly not!" Fatty Coon said.

And he smiled in such a way that he

showed his sharp teeth.

"Somebody stop me, before it's too

late!" Peter Mink cried.

But nobody laid a hand on him. And

still Peter did not move.

"Go ahead!" Tommy Fox urged him.

"You said you were losing your temper,

you know."

"I'm waiting!" Fatty Coon called. And

he held up both his front paws. Peter

saw how strong and sharp his claws were.

"I declare," Peter Mink said, "I haven't

lost my temper, after all. I felt it going—for

a moment. But it came back again."

p. 48

Peter Mink was angry with Tommy Fox;

for it was he who showed everybody that

Peter was afraid of Fatty Coon. Peter

Mink was so angry that he went about telling

everyone he met how he was going to

punish Tommy Fox. "When I finish with

him," he said, "he'll know enough to keep

his advice to himself."

"What are you going to do to him?"

Jimmy Rabbit inquired.

"Well, I'm going to bite his nose,"

Peter explained, "because it was his nose

that he stuck in my affairs." And Peter

went away muttering even worse thingsp. 49

to his cousin, who was with him. His

cousin's name was Slim Mink. And he

was spending the summer in Farmer

Green's haystack near the duck pond.

Slim had heard somewhere that there

was a place called the Reform School,

where boys were sent who fought too

much. And he began to be afraid that if

Peter did to Tommy Fox half the things

he said he was going to do, some one would

come along and catch Peter and send him

to the Reform School.

And the Reform School was an awful

place! Why, boys who went there had to

sleep in beds! They had to wash their

faces every morning, and brush their hair,

and have table manners! It was no wonder

that Slim began to worry.

"You'd better let that young fox alone!"

he told Peter. "You fight too much. If

you don't look out, something dreadfulp. 50

will happen to you, some day. You'll get

sent to the Reform School."

But Peter Mink told him to hold his

tongue. "If you're not careful," Peter

said, "I'll bite your nose, too."

Now, Slim was smaller than his cousin

Peter. And he didn't want his nose bitten.

So he kept quiet after that. But he

hoped that Peter would take his advice.

"Let's go down to the brook and fish,"

he suggested, hoping that he could get

Peter's mind off Tommy Fox.

"You can go if you want to," said Peter

Mink. "And save me some fish, too, or it

will be the worse for you!"

Slim decided that he wouldn't go fishing,

after all. And he roamed through the

woods with Peter, who was determined to

find Tommy Fox.

And at last Peter found him, at a garden-party

that was being given by Jimmyp. 51

Rabbit, in Farmer Green's garden.

Everybody but Tommy Fox was having

refreshments. But he said he didn't feel

like eating anything. That was because

he was polite. He never cared for lettuce,

or peas, or cabbage.

Peter Mink had not been invited to the

garden-party. But that made no difference

to him. Before anyone knew what

was happening he marched straight up to

Tommy Fox and bit him on the nose.

Then there followed such an uproar as

had never before been seen in Farmer

Green's garden. Tommy Fox and Peter

Mink rolled over and over upon the

ground. And for a long time nobody

could tell one from the other.

But after a while that squirming heap

of tails and legs began to turn more slowly,

until at last it stopped altogether.

Peter Mink was a sad sight. He hadp. 52

been ragged enough, before the fight.

But now he looked ten times worse. And

one of his eyes was closed. And he had

lost his hat, and one shoe.

Everyone was glad that the trouble was

over. And everyone was glad that Tommy

Fox had won.

And to everybody's surprise, the gladdest

of all was Slim Mink, Peter's cousin.

"Hurrah!" he cried. (The others had

been too polite to say anything.)

"What makes you shout that?" Peter

asked Slim as he crawled away.

"Why," his cousin answered, "Tommy

Fox hurt you, instead of your hurting

him. And now you won't have to go to

the Reform School."

But for once Peter Mink thought there

might be worse places than that. He

thought that maybe a real bed would feel

pretty comfortable, just then.

p. 53

Peter Mink was feeling even more peevish

than usual. And this was the reason:

Jimmy Rabbit had a new sled.

Now, Peter had never owned a sled;

and it made him envious to see what a

good time Jimmy was having, coasting

down the side of Blue Mountain.

There was only one thing that Jimmy

Rabbit did not like about his sled. It

went so fast that he always fell off long

before he reached the end of the slide.

"I can fix that," Peter Mink told him.

"You go home and borrow your father's

hammer and a few nails, and I'll show youp. 54

how you can coast 'way down into Pleasant

Valley without once tumbling off."

Jimmy thanked him. And he hurried

home at once. He dragged his new sled

after him, too; for he was afraid that if

he left it behind he might not be able to

find Peter Mink—or the sled, either—when

he came back again.

But Peter did not seem to care. Perhaps

he had something on his mind. Anyhow,

when Jimmy Rabbit returned with

the hammer and nails, Peter Mink was

waiting patiently for him.

"Now, then," said Peter, as he took the

nails and the hammer, "you sit on the

sled, Jimmy, and I'll fix you up in no

time."

So Jimmy Rabbit sat down on his new

sled. And in a few minutes Peter Mink

had nailed Jimmy's trousers fast to the

sled.

p. 55

"Now you simply can't fall off," Peter

said. "I'll give you a push; and the first

thing you know, you'll be down in the valley."

Jimmy Rabbit said to himself that

Peter Mink was very bright, to think of

such a splendid plan as nailing his trousers

to the sled. He thanked Peter; and

he gripped the sled tightly—though he

didn't need to—while Peter gave him a

push that sent him flying down the mountainside.

Though he went like the wind, he never

fell off once. And soon he was down in

Pleasant Valley, skimming over the crust

which covered the drifts in Farmer

Green's meadow.

At last the sled stopped. And then

Jimmy Rabbit decided that Peter Mink

had forgotten something. How was he to

get off the sled with his trousers nailedp. 56

fast to it? And what would his mother

say, when she saw the nail-holes in his

trousers? And what would his father do,

when he saw the nails in Jimmy's new

sled?

It was not very pleasant for Jimmy

Rabbit, sitting all alone in the meadow,

with such thoughts running through his

head.

After he had sat there a while Jimmy

heard something that worried him even

more. He heard old dog Spot barking.

And he saw that he would be in a good

deal of a fix if Spot should happen to

come along and find him. For he couldn't

stir from his sled.

Jimmy began to hate that sled. He

wished he had never seen it.... And

then he heard somebody scampering over

the crust. He was almost too frightened

to look around to see who it was. But hep. 57

turned his head. And he was glad to find

that it was Peter Mink, who had run all

the way down from Blue Mountain.

"You had a fine ride, didn't you?" said

Peter Mink.

"Yes," Jimmy answered. "But I liked

the beginning of it better than the end."

"Why, what's the matter?" Peter inquired.

"I can't get off the sled," Jimmy said.

Peter Mink pretended to be surprised.

And he said that he hadn't thought of

that.

"But I'll help you," he promised.

Jimmy Rabbit thanked him.

"But," said Peter Mink, "I can't do

all these things for you for nothing, of

course. I have too much else to do, to be

wasting my time like this, without pay."

"What do you want?" Jimmy Rabbit

asked him.

p. 58

"Give me the sled," said Peter Mink,

"and I'll help you to get off it."

"All right," Jimmy agreed. He would

even have given Peter his wheelbarrow,

too, he was so anxious to be freed from

his seat. "I think, though, that you

might pull me up the mountain," Jimmy

added. "I don't feel like walking." And

that was quite true, because he had been

so frightened, when he heard old Spot

barking, that his legs were still shaking.

"Well," said Peter Mink, "I'm pretty

particular who rides on my sled. But I'll

pull you up the mountain, because I'm

going that way myself, to slide."

And he started off, dragging Jimmy

Rabbit behind him.

p. 59

Peter Mink was pulling Jimmy Rabbit

up the mountainside. You remember that

Jimmy had a new sled, and that Peter had

nailed Jimmy's trousers to the sled, so he

wouldn't fall off when he slid down Blue

Mountain. But when Jimmy had coasted

down into the meadow he found he could

not get off the sled. So Peter Mink had

offered to help him, if Jimmy would give

him the sled in return for his kindness.

"How do you like my new sled?" Peter

Mink asked Jimmy Rabbit, as he stopped

to rest, after climbing a steep slope.

But before Jimmy Rabbit could answer,p. 60

an alarming sound rang through the clear

air and startled them both. It was old

dog Spot, baying as if he had found some

very interesting tracks.

"Hurry!" Jimmy Rabbit cried. "We

don't want Spot to catch us!"

"Get off my sled!" Peter Mink ordered.

"How can I run fast, pulling a great, fat

fellow like you?"

"How can I get off," Jimmy answered,

"when I'm nailed fast to the sled?"

"I'll get you off," said Peter. And he

took hold of Jimmy Rabbit's ears and began

to pull as hard as he could. But the

sled only slipped along on the snow.

"Grab this sapling!" Peter Mink cried,

drawing Jimmy close to a small tree.

"And I'll pull the sled from under you."

But all his pulling did no more than to

make Jimmy's arms ache. For Jimmy

was nailed so fast to the sled that he stuckp. 61

to it—or it stuck to him—as if they were

just one, instead of two, things.

"I wish my mother hadn't made me

wear such stout trousers," Jimmy Rabbit

said. For once, he wished he wore old,

ragged clothes, like Peter's. If he had, he

thought he might have torn himself away

from the sled. But now there seemed no

hope for him, because old Spot's voice

sounded nearer every minute.

At last Peter Mink became so angry because

Jimmy didn't get off the sled that

he flew at him and began to pommel him.

When Peter threw himself upon Jimmy

the sled began to move. But Peter was so

enraged he never noticed that, until they

were coasting down the mountain so fast

that he didn't dare jump off.

Once they struck something. They

couldn't see what it was, because they

were traveling like the wind. But Jimmyp. 62

Rabbit thought he heard a frightened sort

of yelp. Then they tore on again.

Before they reached the foot of Blue

Mountain they struck something else.

This time there was no yelp, for they ran

right into a big maple tree. And Jimmy

Rabbit felt himself sailing through the

air, until at last he landed on top of a big

drift, broke through the crust, and sank

into the soft snow beneath.

He crawled quickly out of the drift.

And when he saw that he and the sled had

parted company he was so delighted that

he never minded his torn trousers.

He looked around. And there was the

sled, as good as ever, except for the nails

Peter Mink had driven into it. And there

was Peter Mink, lying very still beneath

the maple tree. Though Jimmy listened,

he could no longer hear old Spot baying.

That was because old Spot was runningp. 63

home as fast as his legs would carry him.

He didn't know what it was that had

struck him; and he was frightened.

When Jimmy Rabbit saw Peter Mink

slowly open one eye he knew that it

wouldn't be long before Peter was himself

again. So Jimmy hurried back up the

mountain, pulling the sled after him.

The next day, who should come to Jimmy's

house but Peter Mink.

"I've come for my sled," he said.

"What sled?" asked Jimmy Rabbit.

"Why, the one you gave me for getting

you off it," Peter answered.

"But you didn't get me off the sled,"

Jimmy told him. "You don't even know

how I got off. So I certainly am not going

to give you my sled."

And Peter Mink had to go away empty-handed.

He didn't like it at all. But

what could he do?

p. 64

If it hadn't been for the circus posters on

Farmer Green's barn, the idea of having

a circus parade would never have occurred

to Jimmy Rabbit.

You see, all those wonderful pictures set

him thinking. And he lost no time in inviting

everybody to help. He even invited

Peter Mink, though he was sorry, afterwards,

that he had.

For a day or two everybody in the

neighborhood of Blue Mountain was as

busy as he could be, getting ready for the

parade. Cuffy Bear had promised to be

the elephant, because he was so big.p. 65

Frisky Squirrel was to be a wolf, on account

of his being so gray. And Jimmy

had invited Peter Mink to march as a

giraffe, for the reason that he had such a

long neck. And as for Jimmy Rabbit himself,

he said that he expected to be a little

pitcher, because he had heard that they

had big ears.

"I've heard that, too," remarked Billy

Woodchuck. "But I never knew that a

pitcher was an animal."

"Well, you see you have a good deal to

learn," Jimmy Rabbit said.

Then Tommy Fox murmured something

about having heard that little pitchers had

big mouths, too, and that they always

talked a good deal. But Jimmy Rabbit

made believe he didn't hear him.

Everything would have been pleasant,

on the day of the parade, if it hadn't been

for Peter Mink. He insisted that he mustp. 66

lead the procession; and that made trouble

at once, because Jimmy Rabbit had expected

to do that.

Peter finally settled the dispute.

"A parade," he said, "has two ends.

Of course, one person can't march at both

ends at the same time. So while I march

at the front end, Jimmy Rabbit can march

at the other. And that's perfectly fair."

At first Jimmy Rabbit looked quite

glum. But pretty soon he seemed to feel

more cheerful; and he said, "All right!"

Then there was a great bustle, and much

talking, as the parade prepared to start.

"Remember!" Peter Mink warned everybody,

"you must follow everywhere I

go, because I'm the leader."

At that, Cuffy Bear seemed somewhat

worried. He knew that Peter Mink was

fond of squeezing through narrow places;

and he didn't see how he could follow him.

p. 67

But after a while Cuffy began to smile

again—right after Jimmy Rabbit had

come and whispered something in his ear.

You see, Jimmy went to everybody in the

parade and whispered. And last of all he

went to Peter Mink and whispered in his

ear, too.

"Everybody must look straight ahead,"

Jimmy told Peter, "because that's the way

they always do in a circus parade."

"Don't you suppose I know that, just

as well as you do?" snapped Peter Mink.

"You'd better hurry back to the other end

of the parade, because I'm going to start

in exactly two or three minutes—I'm not

sure which."

So Jimmy Rabbit hurried back as fast

as he could. He might have run faster,

if he hadn't stopped to wink at every person

in the line. But he just managed to

reach his place when the parade started.

p. 68

Then a queer thing happened. When

everybody had taken ten steps, the whole

parade turned about in its tracks and

started marching in the opposite direction.

And now Jimmy Rabbit led the procession,

instead of Peter Mink.

I said the whole parade turned around;

but what I meant to say was everybody

but Peter Mink. You see, Jimmy Rabbit

had told Peter not to look back, but to

march straight ahead, with his eyes to the

front. And naturally, Peter Mink supposed

that that was what Jimmy had whispered

to everyone else.

So away Peter Mink marched, trying to

look as much like a giraffe as he could, and

feeling very proud, too—because he

thought the parade was following him.

p. 69

While Peter Mink marched on, believing

that the circus parade was following

him (when Jimmy Rabbit had actually led

it away in the opposite direction), Peter

kept trying to think of some trick he could

play on the parade.

He decided, at last, that he would hunt

around until he found the smallest hole

he could possibly squeeze through, and he

would squirm through it, and then have

fun watching the others try to follow him.

Finally he found a log which lay upon

a rocky ledge. Between the log and the

rock there was a narrow opening. Andp. 70

when he saw that, Peter knew it was the

very place he had been looking for. Without

once glancing around, he thrust his

head through the crack.

Then something happened. Peter Mink

always claimed, afterwards, that the log

settled a bit lower, or the rock rose a bit

higher. Anyhow, to his astonishment, he

found himself stuck fast under the log.

Such a thing had never happened to him

before.

"Well!" he said to himself, "there are

plenty of people here to help me, anyhow."

You see, he hadn't discovered that

the whole parade—except him—had

turned about and followed Jimmy Rabbit.

Peter Mink thought it was strange that

nobody came and offered to help him. And

soon he began to shout.

Still no one came. And Peter began to

wish that he hadn't tried to play a trickp. 71

on the paraders. For he saw that he was

in something very like a trap. In fact, it

was a trap, which Johnnie Green had set.

But Peter didn't know that. If he had, he

would have been even more worried than

he was. It was bad enough, just to imagine

what would happen if old dog Spot

should come along and find him.

Jimmy Rabbit had a fine time leading

the parade. You may be sure he looked

around at the procession following him.

And he shouted a good many orders, too,

telling different ones just what they

should or shouldn't do.

The parade had marched through the

woods for a long time; and Jimmy was

about to stop and tell everybody that the

fun was over, when he saw all at once that

it was really just going to begin. For

right in front of him he saw his friend.p. 72

Peter Mink, pinned fast beneath the log.

"You've been long enough coming to

help me!" Peter Mink growled. "Get this

log off me—you people—and be quick

about it!"

Brownie Beaver left his place in the

parade and hurried forward, because he

knew more about handling logs than anybody

else there. But before he could get

his coat off, Jimmy Rabbit called him one

side and whispered to him. And then

Jimmy whispered to everybody else. And

the parade disbanded. Then everybody

crowded around Peter Mink.

"What is it you want?" Jimmy Rabbit

asked Peter.

"Want?" Peter Mink screamed. "Are

you blind? Can't you see this great log

on top of me? Can't you get it off? What

are you waiting for?"

"Ah!" said Jimmy Rabbit. "We arep. 73

waiting for just one thing. And we

haven't heard it yet."

"Heard it?" Peter Mink snarled.

"Aren't your ears big enough to hear

everything?"

"We're going to teach you something,"

said Jimmy. "And until you've learned

the lesson, we're going to leave you right

where you are."

You should have heard Peter Mink then—or

rather, you're lucky you didn't hear

him. For the way he went on was something

dreadful. But until Jimmy Rabbit

heard what he was waiting for, he

wouldn't let anyone roll the log off Peter.

Finally it grew so late that some of the

paraders said they would have to be going

home pretty soon. And then Billy Woodchuck

remarked that he didn't believe

Peter Mink had the least idea what they

were waiting for.

p. 74

"I think we ought to tell him," Billy

said.

So Jimmy Rabbit told Peter what it

was.

"I don't know what it means," said

Peter.

"Well—say it, anyhow!" Jimmy Rabbit

ordered. "And after this, whenever you

want anybody to do anything for you,

don't forget to say it! It wouldn't do you

a bit of harm to practice saying it every

day, for a while, until you get used to it."

Peter Mink looked as if he would have

liked to do something to Jimmy Rabbit.

And for a long time he refused to obey.

But when Brownie Beaver said that he

simply must go home, because it was so

late, Peter Mink said what Jimmy had

been waiting for.

It was "Please!"

And no doubt you guessed it long ago.

p. 75

"Yes! They say he has at last decided to

go to work," Mrs. Rabbit was saying to

Billy Woodchuck's mother.

"It's the best news I've heard in a long

while," Mrs. Woodchuck remarked. "And

I hope he'll be so busy that he won't have

time to come around here and get our sons

into any more mischief."

"Have you learned what his work is going

to be?" Mrs. Rabbit inquired.

But Mrs. Woodchuck said she didn't

know that. She only knew that Peter

Mink was going to turn over a new leaf

and do some sort of honest work.

p. 76

Now, Peter Mink had a plan. And he

hadn't told any one exactly what it was.

The Grouse boys and the Woodchuck

brothers gave a concert that very night.

You see, Mr. Fox had taught them to make

music like a fife-and-drum corps—the

Grouse boys drummed and the Woodchuck

brothers whistled. And whenever

they gave a concert, almost everybody

went to it.

Well, when the forest-people reached

the hollow where the concert was to be

given, there was Peter Mink, all smiles.

He stepped up to each newcomer and said:

"Check your hat and coat?"

Some of the forest-people didn't know

what he meant, until Peter explained to

them that he would take care of hats,

coats, umbrellas, walking-sticks, or anything

else that anybody might like to leave

with him during the concert.

p. 77

"How are you going to find my hat, if I

leave it with you?" Mr. Rabbit asked.

Peter Mink showed him a heap of oak

leaves.

"I'll tear one of these in two," he said,

"give you half of it, and stick the other

half inside your hatband. When the concert

is over and you come away, all you

have to do is to hand me your half of the

oak leaf and I'll see which piece matches

it among those that I have kept. And the

hat in which the other half happens to be

stuck must be your hat. Do you understand?

It's quite simple," Peter said.

Mr. Rabbit said that he understood, and

that it was a good idea, too. But he

thought he'd keep his hat with him.

Then his wife said to him in a low voice

that he ought to do whatever he could to

help Peter Mink.

"Now that Peter has gone to work," shep. 78

told her husband, "everyone ought to encourage

him. And I want you to leave

your hat with him. I'll have him check my

spectacles, as he calls it," Mrs. Rabbit

added, "for I shall not need them. I can

hear exactly as well without them."

Mr. Rabbit always tried to please his

wife. So he let Peter Mink check his hat.

But he felt uncomfortable during the

whole concert. It was a new hat. And he

didn't like the thought of losing it.

That same thing happened in a good

many families. Most of the gentlemen

said that Peter's idea was a good one, but

they thought they would wait till another

time. And their wives generally persuaded

them to let Peter Mink check

something, just to help him along.

But Uncle Jerry Chuck refused to leave

a single thing with Peter. He said he had

had his hat for a great many years.

p. 79

The music was not so good as usual that

night. And when the fife-and-drum corps

played "Pop! Goes the Weasel!"—which

was their favorite tune, and the first they

had ever learned—they had to stop in the

middle of it three times, and begin again,

because there were so many interruptions.

People kept standing up in their seats and

looking around to see if Peter Mink was

still there. And almost everybody except

Uncle Jerry Chuck seemed worried.

But Uncle Jerry had a fine time. You

see, whenever the fifers and drummers had

to stop, and begin again, Uncle Jerry felt

he was getting more music. And he enjoyed

it especially because he had found

his ticket in the woods and didn't have to

pay for it. And on account of what happened

when the concert was over, Uncle

Jerry was even happier the next day.

p. 80

The concert given by the Grouse boys and

the Woodchuck brothers came to an end

early. Billy Woodchuck, who was one of

the fifers—because he was such a good

whistler—made a short speech.

"We shall have to stop now," he said,

"because so many people keep bobbing up

and looking around that they make us

nervous. Maybe the piece we just played

didn't sound quite right. So I want to

explain that each of us was playing a different

tune, we were so upset. And, of

course, we can't keep on." Then he made

a low bow.

p. 81

All at once there was a great rush

toward the place where Peter Mink was

waiting, with the hats and sticks, umbrellas

and spectacles, coats and rubbers, and

other things that he had checked for the

people who came to the concert.

When Peter Mink saw everybody hurrying

up all at the same time the smile

faded from his face.

"Don't crowd!" he begged them.

"There's something here for everybody."

He took the half oak leaf that Mr. Rabbit

handed to him and hunted around until he

found another half that seemed to match

it. And since that other half was stuck in

an old umbrella, he gave the umbrella to

Mr. Rabbit.

"But I didn't leave an umbrella with

you. I left a hat!" Mr. Rabbit cried.

Peter Mink shook his head.

"You must be mistaken," he replied.p. 82

"You said yourself my idea was a good

one, you remember."

Now, Mr. Rabbit didn't intend to lose

his new hat. So he began to hunt for it,

though Peter Mink told him to stand back.

That was only the first of a number of

disputes. There was Mr. Woodchuck—he

had left his favorite walking-stick with

Peter; and all he received in its place was

one worn-out rubber and one mitten with a

hole in it.

Old Mr. Crow made a terrible noise

when Peter Mink tried to make him take

an overcoat that was at least four times too

big for him. And Peter insisted on attempting

to squeeze Fatty Coon into a

coat that was twenty-three sizes too small

for him, and which really belonged to

Sandy Chipmunk.

There was such an uproar, with all the

people complaining, and trying to findp. 83

their own things, that Peter Mink began

to think he had better leave before he

found himself in worse trouble. So he

slipped away. And nobody noticed that

he was gone, because there was such confusion.

It was a long time before everybody

went home. And even then there were

many who weren't satisfied. For instance,

there was Mrs. Rabbit. To be sure, she

found a pair of spectacles. But they

weren't the ones she had given Peter.

And she couldn't see through them very

well.

Uncle Jerry Chuck did everything he

could to help. He pushed right in where

the crowd was thickest and pawed over

everything he could find. There were

some unkind people who objected, and

said that he had no business there, because

Peter Mink had checked nothing for him.

p. 84

But that made no difference to Uncle

Jerry. He wouldn't leave until he was

ready to go. And the next day he appeared

in a brand new hat. He said that

his old one had really become shabby. But

whenever any one asked him where he

got his new hat he pretended not to hear,

and hurried away. And after that people

liked him even less than they had before.

As for Peter Mink, he never tried to

work again. Some of the forest-people

said that he had never meant to work, anyhow.

They claimed that he had mixed up

everything on purpose, to play a trick on

people. And for a long time no one saw

Peter Mink in that neighborhood.

Mr. Rabbit said that that was the only

pleasant part of the whole affair.

p. 85

Perhaps you never heard how Mr. Mink

lost his tail in the woods, and how Jimmy

Rabbit found it and wore it until Mr.

Mink came along and took the tail away

from him.

Peter Mink knew all about it, anyhow,

for Mr. Mink was his uncle. And Peter

knew that Jimmy Rabbit was still on the

lookout for a fine, bushy tail.

So one day when Peter met Jimmy Rabbit

he told Jimmy that if he would go to a

certain place, near Broad Brook, he might

find something that would interest him.

"You'll find a small place where thep. 86

earth has been stirred up," Peter said,

"if you look exactly where I tell you to.

There's something hidden there. And I

won't say just what it is. It might be a

tail; and then again, it might not," Peter

told him. "Anyhow, if you go and dig

in that spot, I know you won't hurry

away, when you find what's there."

Now, Jimmy Rabbit ought to have

known Peter Mink well enough to suspect

that there was something wrong. But the

moment he heard the word "tail" he

couldn't start for Broad Brook fast

enough.

It took him some time to find the place

Peter Mink had described, for a light

snow had covered the ground. But at last

Jimmy discovered the loose earth, exactly

as Peter had said.

Jimmy Rabbit was just going to begin

to dig when some one called his name. Andp. 87

he jumped back quickly and looked all

around. At first he could see no one. But

after a moment he saw some one beckoning

to him. It was Paddy Muskrat. He had

crawled out of the brook just in time to

stop Jimmy Rabbit before it was too late.

"What are you going to do?" Paddy

Muskrat asked.

"I'm going to dig in this dirt," Jimmy

explained. "I believe there's a tail hidden

there. I need one, you know. And Peter

Mink told me——"

"Peter Mink!" Paddy interrupted.

"I'd advise you to have nothing to do

with Peter Mink. Because sooner or later

he'll get you into trouble.... Do you

know what's hidden beneath that dirt?

I'll tell you: it's a trap! Johnnie Green

set it there, thinking he could catch me in

it. But I saw him when he buried it. And

I wouldn't go near it for anything."

p. 88

As soon as Jimmy heard the word

"trap" he couldn't get away from that

place fast enough. He turned and ran off

in great bounds; and he never even stopped

to thank Paddy Muskrat for warning

him. Now, that was not like Jimmy at all.

But you see, he was frightened.

Paddy Muskrat was a wise little chap.

And though he had said he wouldn't go

near the trap for anything, he thought it

was about time somebody fixed the trap

so it couldn't do any harm. And very

carefully he scraped the dirt away from it.

"There!" he said to himself. "Now

everybody can see it. And no one will get

caught." Then he jumped into Broad

Brook again and swam away.

Not long afterwards a slim figure came

stealing through the woods. It was Peter

Mink; and he had a bag in his hand. He

expected to use the bag, too. For he wasp. 89

very sure that he would find Jimmy Rabbit

fast in the trap and he intended to

put him in the bag and drag him away.

Peter was disappointed when he saw

that the trap was empty. And he wondered

what had happened.

"Well, here's the bag, anyhow," he said

to himself. "I've got that!" And he sat

down and made a hole in the bag for his

head, and two more for his arms, and drew

the bag on. It fitted him very well.

"Why, here I've a new coat!" he said.

"I see now that the bag would have been

much too small to hold Jimmy Rabbit. So

it's just as well he didn't get caught in the

trap."

And Peter Mink walked away. He liked

his new coat But probably it wasn't the

kind you would care for at all.

p. 90

Sometimes Peter Mink grew tired of

not knowing where he was going to sleep.

And now and then, when he happened to

be in some neighborhood that he liked, he

would try to find a place where he might

stay until he felt like roaming on again.

There was one neighborhood that Peter

liked very much. He often said that of all

the places in Pleasant Valley that he knew

anything about, there was no other as

charming as Farmer Green's duck pond.

The reason for his thinking that was

that he was specially fond of duck meat.

And, of course, it was convenient to bep. 91

able to swim under water, and steal upon

a fat duck, and seize her before she knew

that Peter was anywhere near.

Now, Peter Mink learned that there was

a muskrat who had built him a house in

the bank of the duck pond. And as soon

as Peter found out where the muskrat's

home was, he drove away the owner and

began to live in the house himself.

He found it very comfortable. And he

caught a duck every day, until at last

Farmer Green noticed that his ducks were

disappearing.

"I believe it's a mink that's taking

them," Farmer Green said to his son

Johnnie. "If it was a coon, he'd steal

more than just one a day.... Now, you

take the old gun and go down to the pond

and hide. And when I let the ducks go

out for their swim, I want you to watch

for a mink."

p. 92

Naturally, Peter Mink didn't hear what

Farmer Green said. If he had, no doubt

he would have left the muskrat's house at

once and moved on to some other neighborhood.

Early the next morning Johnnie Green

put the old gun on his shoulder and stole

down to the edge of the duck pond, where

he hid among some cat-tails. He kept his

sharp eyes on the bank of the pond, for

the ducks were just waddling down from

the barnyard, to enjoy their morning

swim.

As sharp as Johnnie's eyes were, they

did not see Peter Mink as he crept out of

his house and stretched himself in the sun.

Peter had fallen into the habit of sleeping

late and awaking each morning just as the

ducks reached the pond.

He saw them as they picked their way

down the bank. And for once he didn'tp. 93

seem to care anything about them. To

tell the truth, he had breakfasted on duck

so often that he had at last grown a bit

tired of duck meat. And now he thought

that for a change an eel would taste good.

For the first time since Peter had driven

the muskrat from his home the ducks were

safe.

Peter paid no attention to them. And

unnoticed by Johnnie Green, he slipped

into the water and swam quickly to a place

in the pond where there was a warm

spring. He knew that the warm water

rose to the top of the pond. And he knew,

as well, that if an eel should happen to

swim over the spring, the rising water

would bear him to the surface of the duck

pond.

Peter Mink must have been a lucky fellow.

For he had hardly reached the

spring when he saw an eel right in front ofp. 94

him. He seized the eel and swam toward

the bank. And there was such a commotion

in the water that Johnnie Green

couldn't help noticing it.

You see, the eel did not want to leave

the duck pond. He had always lived there,

and he liked it, too. So he twisted and

squirmed, trying his hardest to break

away from Peter Mink.

But Peter swam steadily on, though to

be sure he couldn't swim very fast, dragging

such a slippery fellow along with

him.

But finally he reached the shore. And

then he pulled the eel out of the water.

Still the eel tried to get away from him.

He wound himself about Peter Mink.

And several times he managed to throw

Peter head over heels. But Peter Mink

always rushed upon the eel again before

he could wriggle into the pond.

p. 95

All this time Johnnie Green had entirely

forgotten about his gun. He had

never seen such a sight before. And he

looked on with staring eyes, until at last

Peter dragged the eel away from the pond

and into some bushes.

Then Johnnie Green remembered why

his father had sent him down to the duck

pond. And he ran forward, all ready to

shoot.

But Peter Mink had vanished. He had

heard Johnnie running; and that was

enough to send him skipping away.

Peter was disappointed, because he lost

his breakfast. And Johnnie Green was

disappointed, because he lost Peter.

In fact, of all those present, the ducks

seemed to be the only ones that were really

contented. They had a fine swim. And

when night came, not one of them was

missing.

p. 96

There was one thing that Peter Mink

couldn't understand. No matter how hard

he tried to get Jimmy Rabbit into trouble,

Jimmy always managed to escape. Peter

wondered what the reason might be. And

one day he said to Jimmy:

"Why is it that you're always able to

get out of a scrape?"

"Don't you know?" Jimmy Rabbit

asked him. "I thought everybody knew

that.... It's because I'm lucky."

"Oh, I know that!" said Peter Mink.

"What I'd like to know is what makes

you so lucky?"

p. 97

"I supposed everybody knew that, too,"

Jimmy Rabbit answered. "It's because I

have the left hind-foot of a rabbit."

Peter Mink answered that he didn't see

what that had to do with being lucky.

"You ask anybody about it," Jimmy

told him. "There's Mr. Crow, over on the

fence. Go and ask him why I'm lucky."

So Peter Mink went over to the fence

where Mr. Crow was resting, and put the

question to him.

"Oh, ask me something hard!" Mr.

Crow cried. "That's too easy. Everybody

knows that one."

For once Peter Mink remembered the

word Jimmy Rabbit had taught him when

he was caught beneath the big log.

"Please!" he said. "I'd really like to

know, Mr. Crow!"

"Left hind-foot!" Mr. Crow replied

briefly. "It's a rabbit's, you know; andp. 98

there's nothing like 'em to bring luck."

That set Peter Mink to thinking. He

couldn't help wishing that he might have

Jimmy's left hind-foot for himself. It

ought to bring luck to him, he thought,

just as it did to Jimmy Rabbit.

After Peter Mink had thought the matter

over for some time, he said to Jimmy:

"I wish you'd come over to the creek

with me. There's something there that I

want to show you. Of course, it's a long

way off; and maybe your mother wouldn't

like to have you go so far from home."

"I'll come!" Jimmy Rabbit said quickly.

"Maybe you'd better ask your mother

first," Peter suggested.

But Jimmy Rabbit shook his head.

"That wouldn't do any good," he replied.

"Let's be on our way!"

So Peter Mink started off toward the

creek, with Jimmy close behind him.

p. 99

At last they reached the bank of the

creek. The water was low. And before

them was a stretch of mud, which looked

dry and firm. There were a few weeds

growing in it. And it certainly looked

harmless enough.

"What is it you're going to show me?"

Jimmy asked.

"Follow me!" said Peter Mink. "You'll

see pretty soon what it is." And he

jumped off the bank and landed lightly on

his feet on the mud-flat, and started on

again.

It never once entered Jimmy Rabbit's

head that there could be any danger. So

he jumped off the bank, too. And to his

great surprise his legs sank entirely out of

sight in the mud.

You see, he was at least four times heavier

than Peter Mink. And when he landed

on the thin, sun-baked crust that coveredp. 100

the mud-flat he had broken through it.

Jimmy Rabbit had a terrible feeling

that he was going right down until the

mud closed over his head.

"Help!" he shrieked. "Help! Help!"

But Peter Mink walked straight on. He

never once looked around.

And though Jimmy Rabbit called and

called, he couldn't seem to make Peter

Mink hear him.

p. 101

Stuck fast in the mud as he was, Jimmy

Rabbit couldn't do a thing except shout.

Or you might spy there were only two

things he could do—shouting being one of

them, and keeping still being the other.

At first, Jimmy couldn't help calling out

at the top of his lungs. But Peter Mink,

you remember, didn't appear to hear him.

And there seemed to be no one else near.

After a time Jimmy Rabbit grew so hoarse

that he stopped shouting for help and

tried to think of some way in which he

might escape.

It occurred to him that if he could onlyp. 102

manage to get his left hind-foot free of

the mud (that was his lucky foot, you

know) perhaps he would be able to crawl

out, somehow. With his lucky foot buried

deep in the mud, and quite out of sight,

Jimmy thought it was not at all strange

that he had not been able to free himself.

So he tried to raise his left hind-foot.

At first the mud actually seemed to suck

it deeper, as he tried. But after a long

time Jimmy succeeded in lifting that foot

the least bit. And he was pleased—until

he discovered that his other hind-foot had

only sunk further into the mire.

At last he happened to look up. And

there on the bank, gazing down at him,

stood Peter Mink.

"What are you doing down there?"

Peter Mink called. "Why didn't you follow

me, as I told you to?"

"I fell into this mud," Jimmy Rabbitp. 103

told him. "And I called and called to you.

Couldn't you hear me?"

"The wind was blowing," said Peter—and

anyone can see that that was no answer

at all.

"Well, if you'd looked around, you

could have seen what happened to me,"

Jimmy Rabbit complained.

"The sun was shining in my eyes,"

Peter Mink told him—and I shouldn't say

that this answer of Peter's was any better