MAKING LIFE

WORTH WHILE

By

DOUGLAS FAIRBANKS

Author of “Laugh and Live”

New York

BRITTON PUBLISHING COMPANY

Copyright, 1918, by

Britton Publishing Company

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | Little Grains of Sand | 13 |

| II | As the Twig Is Bent | 23 |

| III | The New Order of Living | 31 |

| IV | Feeding the Intellect | 41 |

| V | Backing Up the Flag | 49 |

| VI | Half-Baked Knowledge | 57 |

| VII | Harnessing the Brain | 65 |

| VIII | Exalting the Ego | 73 |

| IX | Genius Plus Initiative | 81 |

| X | The Big Four | 87 |

| XI | Applying the Rule of Reason | 95 |

| XII | Through Difficulties to the Stars | 109 |

| XIII | In Answer to Many Friends | 115 |

| XIV | Things That Money Won’t Buy | 127 |

| XV | The Boy Across the Sea | 133 |

| XVI | Superior—Superiority—Super | 139 |

| XVII | When the Boys Come Home | 147 |

| XVIII | Regeneration | 153 |

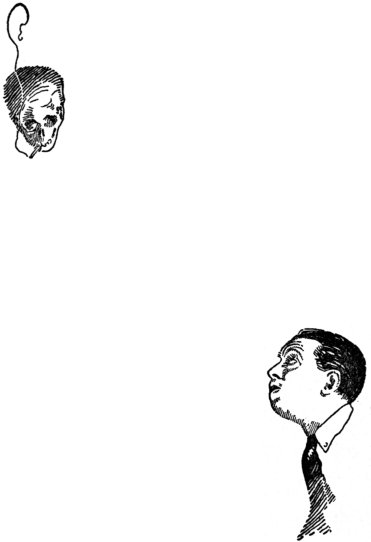

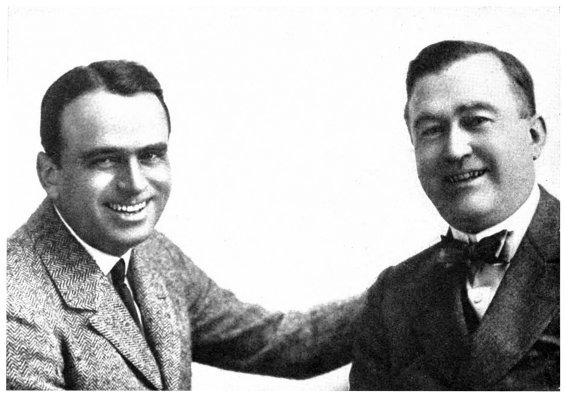

A Modern Musketeer—(Frontis)

——and his brother John

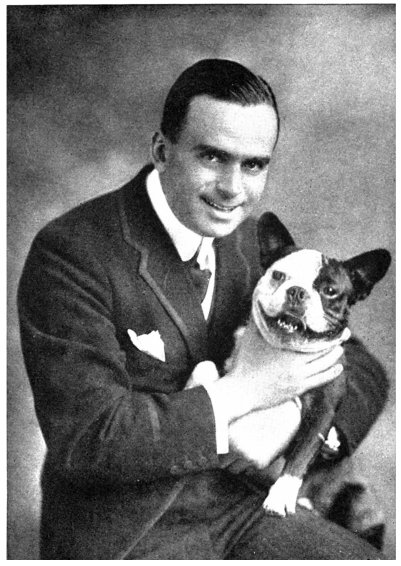

Teaching his dog to smile

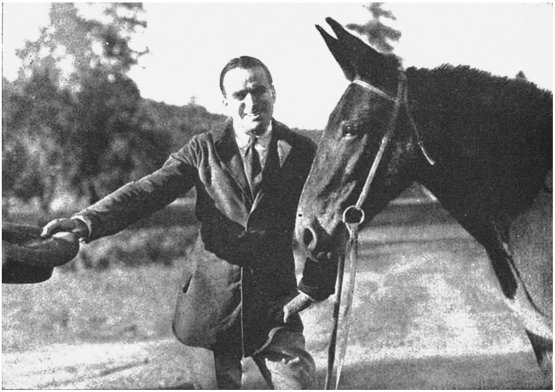

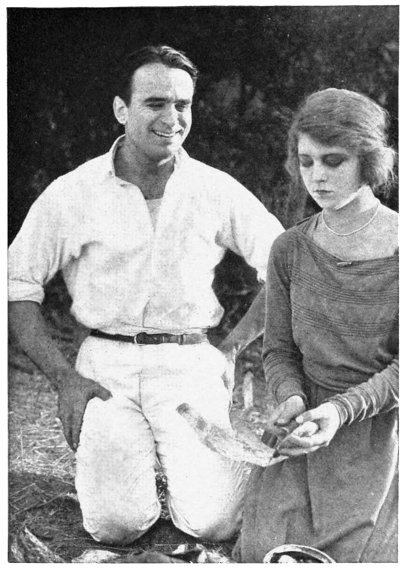

“And her name is Maud”

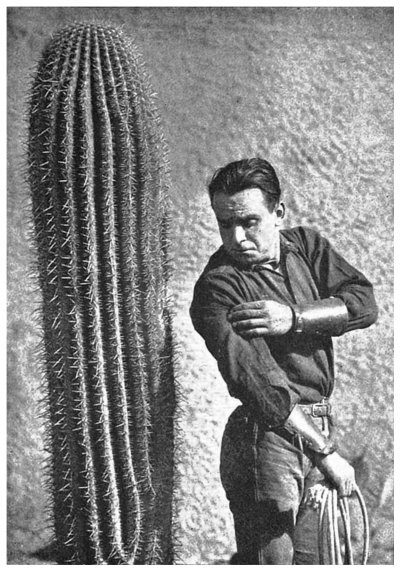

A pointed argument

“Smile when you say it”

Companions

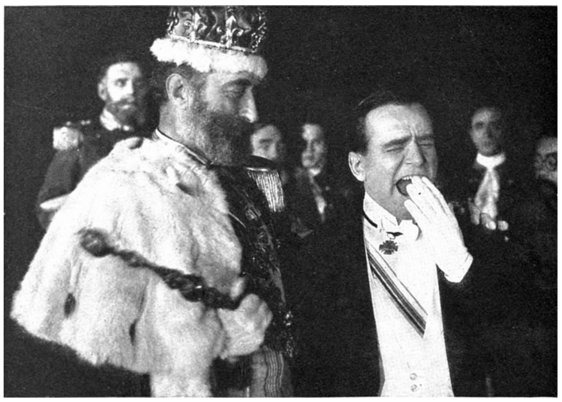

“What ho!” says the King. “Ho, hum!” replied his guest

Tweedle-dee—Tweedle-dum

Where once one equals two

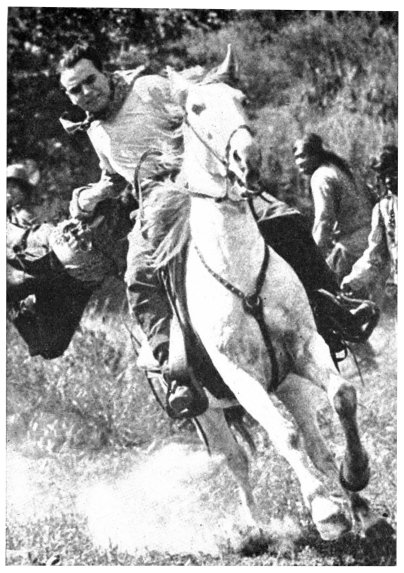

A quick getaway

A rattling good story

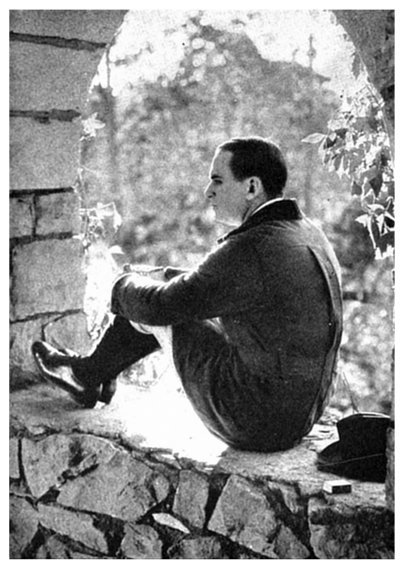

A one-minute reverie

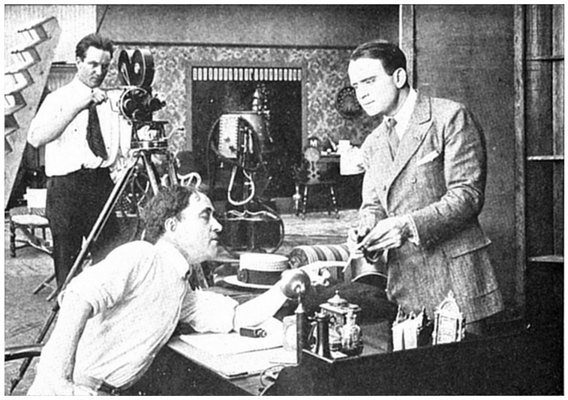

A studio confab

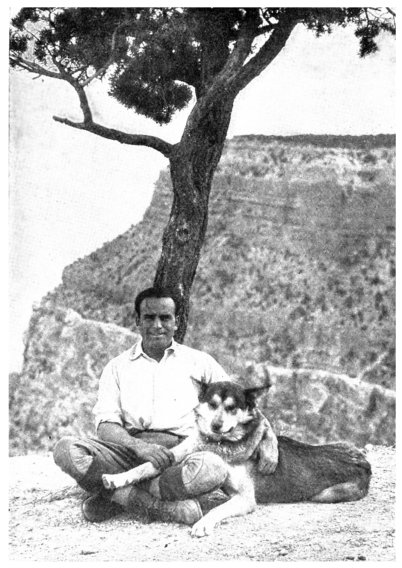

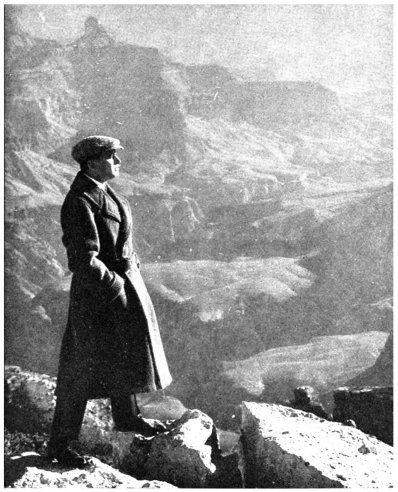

Alone with the Grand Canyon

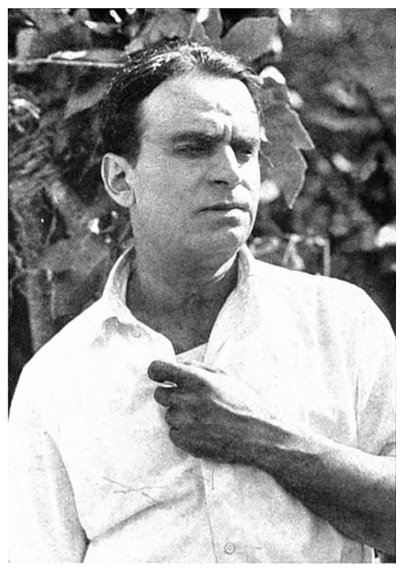

“In tune with the Infinite”

Decorations by Harold A. Van Buren

In Laugh and Live, my sole purpose was to emphasize our first duty toward ourselves, which consists of doing our level best at everything we undertake, and making the best of every situation that arises to confront us.

All through my early life I read inspirational books and liked them best of all. They seemed to beckon me on. I could feel myself being pulled along by an unseen hand.

Let there be no mistake about Making Life Worth While. It has no particular plan or sequence whereby to back up its title. Nearly everything has to do with such a subject and that is what the book contains—everything in general—and nothing in particular—just such things as came to mind that seemed worth while.

As a follow up to Laugh and Live here’s hoping that it will fill the bill.

D. F.

Holding down a seat in the rocking chair fleet out on the shady piazza is most certainly not making the most out of life.

We all remember the line—“If wishes were fishes we’d have some fried.” That is the answer to those who rock and dream, and hope for something to turn up instead of turning up something on their own account.

Of course, there is a time for everything, even the stealthy, creeping rocking chair—and that’s about bedtime. In the estimation of an eminent neurologist there is no crime against nature in the home that cannot be traced to this monstrous thief of time, which,14 while apparently screeching and groaning under its load, is, in reality, shouting with joy at the job it is putting up on its occupant.

Taking the most out of life is the proper label for this old squeaker—breeder of idle contentment, day-dreams, inertia. Like everything else that saps the energy from mind and body, it counts its victims by the score, and throws them up on the sands of time.

Speaking of sand may serve to remind the reader of a well-known poem handed down from Grandmother days, which holds a lot of precious wisdom—probably more than any poem of its length—its breadth and depth being equal to the world in which we live. In childhood days this poem took my fancy, being short, to the point, and easy to15 remember. I was ready to recite it immediately and automatically upon request. I had no thought then as to its meaning, but as the years rolled by it tagged along in memory until now I find in it a sort of statement of fact upon which to build my theory of making life worth while. Here it is:

To those who adopt the idea of finding out just why little drops of water and little grains of sand accomplish so much, will come the greatest reward in the way of mental satisfaction—and, meanwhile, they’ll keep busy.

16 There is unbounded happiness in the pursuit of knowledge; a wonderful satisfaction in building up one’s treasure house of information. It’s all so easy, requiring nothing more than a healthy, enquiring mind—and a zest for the sport.

Zest is a big word. It has to do with get up and git, which has been most appropriately boiled down into the word pep. Lazy people, mentally or bodily, seldom get anywhere. What they do get is either accidental or by absorption—if by the latter process, more likely through the pores than the brain. No use to talk to them about making life worth while.

The greatest of human possessions are a well-trained mind, a body to match, and a love of achievement, without which a man is old before his time. After that comes energy—the great propeller! What the brain directs17 the body will carry out—if the propeller is working. No hesitation—when the will commands the body acts. They synchronize—they are attuned, harmonious, fraternal, so to speak. And to hitch them together is just as easy as getting wet by standing bareheaded in the rain.

There is no intention of littering up this chapter with ways and means of putting one’s upper story in fine working order—or the physical structure below. That is first-reader information. If we treat ourselves right, the brain will behave and the body will follow suit. Activity, mental and physical, is the meat in the cocoanut. Seeking knowledge leads along the sunlit paths of life where happiness abounds. The alternative is mental shiftlessness, leading from nowhere to nothing at all.

Cain killed Abel because, undoubtedly, of18 the shiftless life he led. Indolence and ignorance being the order of his day, he lacked the stamina with which to control his mind. His physical forces merely acted in consonance with his rage at Abel’s popularity. Cupidity led him on, but if Cain hadn’t lost his head through lack of will to control himself the example of murder might never have been set before mankind.

Centuries have come and gone and still the passion to kill continues upon the face of the earth. To stop it is but a matter of correcting human thought through physical and mental training so that those notions which interfere with a normal, healthy brain tendency, will cease to exist. This done, the degenerate born of indolence somewhere along the line, will disappear from the face of the earth in jig time.

19 New intellectual forces will do the trick; forces built up from healthy, right thinking, energetic investigation, and consequent acquisition of knowledge.

How the world will wag a few years hence depends upon Mothers and Fathers of today. As great trials are strengthening to character, the prospect seems bright.

Temperament looms large in the game of life, and, like all other human brain tendencies, is subject to regulation through the exercise of ordinary horse sense. We often hear one person speak of another’s temperamental qualities in the light of an incurable disease, and more than likely in an apologetic way. A faulty tendency is usually laid at the door of a doughty grandsire on one or both sides of the house and left there as a piece of ordinary table gossip to be resumed any old time without notice.

We’ve all heard someone dispose of another with quick dispatch by the casual remark,24 “He’s temperamental.” It all depends upon the inflection of the speaker’s voice whether his words are intended as a knockout blow or an apology in behalf of the culprit. But any time you want to pursue the subject you’ll hear about some obdurate old ancestor who passed the buck on to his posterity.

While we most assuredly do inherit various mental attitudes from our ancestors, there’s nothing we cannot get rid of if we resolve to do so. There is nothing fatal about preconceived notions handed down to us. Mental culture through education and association is the royal road. If, through ignorance, or narrow-mindedness, one should prefer to hang on to certain personal or mental crudities just for the sake of posing as a “chip off of the old block,” then let the punishment fit the crime.

25 Temperament plays a big part in making life worth while and is more largely due to the time in which we live and with whom we associate than to inheritance. It is the physical department that is really handed down to us—the blood in our veins rather than the dents on our brains. To be subject to scrofula from infancy is no fault of our own, but to continue an eccentricity under the claim of inherited temperament is excusable only upon the score of ignorance.

People do inherit brain tendencies, but they are all subject to control through the will to do or don’t, as the case may be. Supposing grandfather used to swear like a trooper—and he probably did—the habit was temperamental to the extent of being in tune with the times in which he lived. But what grandson of to-day would think of claiming26 exemption by reason of inherited temperament if addicted to the same vulgar habit? On the other hand, if we are born with rheumatic tendencies we may expect to fight with them all our lives. One is a brain tendency, subject to control; the other is a blood-inheritance that we may never correct.

Personal habits of thought or action are temperamental according to the avidity with which we cling to them. George Ade has said that a man might be born with a hair lip or a club foot, but whiskers were his own fault. Thus we were handed the best possible line of demarcation between the inherited tendency and the personal temperament. So, if we were of the temperament to wear a beard because our great grandfather wore one we could, if the notion struck us, take it to the barber and have it cut away. Just so27 we may get out from any other temperamental habit, or thought, or action, through the very simple process of becoming masters of our own minds. Grandfather may hand us a line of tainted blood that we can’t manage, but temperament is our own to manage as we will.

Control over one’s temperament is positively necessary in making life worth while. If we are bent on securing full happiness for having lived, we are bound to contribute our share toward an ultimate world sanity in which the word temperament may not serve to cloak mental deficiency. College life takes the kink out of the untrained mind and makes it behave normally. It makes no allowance for the accentuated temperament. Fool notions brought along from the dear old home town are soon sifted into the chaff barrel and common sense comes into its own.

We’re never old until we think we are—this I say, not as a sop to those beyond the half-way station, but as a conclusion after some years of observation and association with men.

I know some young men of sixty who are putting over a sample of golf that annexes my goat. One forgets their age when he finds them up and coming on every proposition of legitimate sport and pleasure. They’ve learned how to live and are living.

There is a big change in the habits of men. The day in which we live is replete with simple enjoyments and facilities whereby to32 make the most of them. Achievement keeps them young, and achievement is a matter of management rather than working hours. Organization cuts the hours off of the business day which leaves ample time for the recreation needed to insure a good appetite, a healthy body, and the right kind of sleep. If there is any secret in this simple process then consider that the cat is “out of the bag.” It’s yours.

If we see a lean, hungry, decrepit mule wearily dragging his load along we know at a glance that he is underfed, overworked, and doesn’t receive proper care. He works too many hours a day, stands abuse from his driver, becomes morose, just the same as a human being, and finally, indifferent to what happens. Thus reduced to the depth of despair, he actually awaits the crack of the33 whip across his loins before answering the call to move along.

But times are changing for both men and mules. Neither will stand the abuse and neglect of years gone by. Men are no longer the slaves of the big boss. They have certain hours for work, after which their time is their own.

Fortunately the era of treating one’s self decently is on. The barroom has ceased to be the national indoor sport. Every self-respecting town or city has joined in the community of interests theory that out-of-door life is good for its citizens. The result is play-grounds for children, public parks for all of the family, and golf courses nearby for the men. It beats the old front porch rocking chair proposition forty ways.

It isn’t more than twenty-five years since34 the real out-of-door era began to dawn. I remember distinctly as a boy of ten how hard it was to raise a companion after the evening meal. My parents held liberal views on the subject. They trusted me in the matter of keeping out of mischief and about the only warning I received was, “Don’t go far, and don’t stay out too late.” With such elastic instructions I had very little trouble in keeping the record straight, for my parents never held me to strict account.

In my meanderings, however, I found the boys of my acquaintance pretty well hemmed in during the evening hours. The scene is easily recalled. The front stoop is plastered with rugs; the mother, father, sisters, aunts, and grandmother are seated about on the steps, hammock or porch chairs. Bob, Bill, Dick or Jim, as the case might be,35 was first to be noticed leaning against the front gate, or looking dreamily over the side fence. But as soon as the porch arguments began to warm up he could be seen edging along slowly, inch by inch, toward the rear—just nonchalantly, two pickets at a time, without any special semblance of hurrying. If his mother had the floor in the argument he got away speedily and he generally waited for that.

But success was not always the case. Many times have I stood impatiently out of view giving the hurry-up signal, when suddenly there came a loud call from the front that caused Robert to fall back into his own yard and walk quickly around to the whenceness of the clamor.

“What do you want, Ma?” he would enquire—as if he didn’t thoroughly well know.

36 “I want you to stay around here where I can keep an eye on you. Then I’ll know where you are.”

Sometimes this kind of a backset would require nearly a half hour of skilful jockeying to repair. After that only the boldest of plans stood a chance to succeed, such as walking into the house from the front as if in deep disgust, or after a drink of water in the rear of the house. Then out through the kitchen door and over the back fence in a jiffy.

A nudge from sister often nullified this subterfuge when the mother seemed about to fall for the project, and that meant the loss of another fifteen minutes during which Bobby would actually go and take a swallow of water and come back to the porch, there to stretch and yawn until told that he’d better37 go in and go to bed. Victory at last for Bob, showing that there was more than one way to win a battle even in those days. The slamming of an upstairs bed-room door, meant for his mother’s ears, a slide down the “rain pipe”—and over the fence for Bobby.

But what a wonderful change has come into the parental mind since then. Now all Bob does is to announce where he is going—to the “gym,” over to Bill’s, motor-boating, canoeing, bicycling, a hike in the park, or a look in on the movies. Home and to bed by ten o’clock.

And what is the result? Boys of twelve now days become officers in Boy Scout companies. They go in for everything likely to make them athletic, manly and alert. At sixteen they have more general knowledge than boys of twenty had twenty-five years ago.38 And their minds are cleaner, likewise their bodies. Schooling comes easier to them, although the courses are far more advanced. It takes knowledge to get started off right now days.

This is an age of pep, and the competition of today means pep vs. pep. With equal mental preparedness the man with the brawn will stand the gaff that would kill his soft competitor. Lest we forget—recreation, a good appetite, a healthy body, and the proper amount of sleep—are positive requirements in making life worth while.

Feeding the intellect is naturally the most fascinating pursuit in this life and probably will be in the life to come. There is nothing like stocking up the mind, tickling the brain cells, making dents in the cerebellum, for thereby is induced the most perfect sanity and the power to think with precision.

It is bully to be able to think straight to the point, and to quickly analyze right down to the bone. Such ability loans us proper respect for ourselves and compels the respect of all with whom we may brush against.

Power to think begins with first realizations, and thereafter we have only to add fuel42 to the intellectual fires day by day, month by month, and year by year, until we arrive at that state of mental sufficiency which may happily be termed “the fullness thereof.”

Not until we cross this bridge are we safe—not until then will we have come into a state of sane thinking—nor will we be fully alive! On our march we will have learned to delve with patience, listen with understanding, and communicate with intelligence. Then we may give and take with common understanding with the best of them. What we get we store away for use when needed. Then may we commune with our intellectual equals on the basis of quid pro quo—horse and horse—“even Stephen.”

But what a heartache when we cannot give! What a sensation of regret when we find ourselves standing still intellectually43 while we watch the procession go by. Not capable of giving, likewise we are handicapped in our ability to receive—we’re hitched to a post, so to speak, along with other species of lesser understanding.

Alongside of us in our journey through life are sure to be men of more than ordinary achievement, who by dint of special genius have accomplished worthy objects most passing well—something that brought them wealth or fame and likely both—but left them dumb and speechless in the presence of intellectual persons, who, in self-defense, must pass them up for want of mental fellowship.

To speak of the “Dark Ages” is but a polite reference to that period of time when mankind generally was known to be “addle-pated.” The light refused to shine upon his44 thimbleful of brains, although the sun of centuries had blazed down upon a world of half-baked intellects—and even yet has work ahead. But coming through the ages, in the due course of events, a few master minds coincided in the belief that a little exercise was good for the “noddle” and set about it to experiment.

The first hard work indulged in by our early ancestry, after receiving a slight smattering of instruction, was to kill off their teachers. Many centuries were allowed to skip by before education was again utilized in stimulating the understanding.

Pending the dawn of the new era, man was taught only the use of his hands and feet for the sake of his stomach—his upper story becoming a warehouse for dark superstitions, and fearful forebodings. It is not unlikely45 that from this period descended the later day reference to certain persons as numskulls—a species of mankind known to have bats in the belfry.

Notwithstanding the seeming uselessness of many hundreds of centuries in their relation to human intelligence, there is no discounting the fact that we have finally come into an age when brain power is not counted a misdemeanor and made subject to fine and imprisonment. From the end of our Civil War to the breaking out of the great world-wide strife, the intellect of man had expanded tremendously. More important still, intellect had been discovered to be a world-asset, and of such mighty consequence that human knowledge progressed amazingly.

Pity it is that the world’s brain power could not have forestalled the great slaughter—impossible,46 however, at this stage of our mental development. But the time is coming—our grandchildren will see the day—when intellectuality will rule the universe. Brains and bodies of individuals are to be developed for other uses than war. Until that day arrives we are bound to continue as before, and will, with true patriotism, follow the flag of our cause.

Some day when our intellects have been fed up into a higher state of efficiency and humanity is more nearly matched in brain power, settlements between nations will be made beside the lamp of reason rather than under the flare of the cannon’s mouth.

Loyalty is one of those three-syllable words with a big meaning all its own. Out of the letters composing it can be spelled two other words—the preposition to; and the adverb all. Loyalty to all—everything worth while; our country, our homes, our government, and the friends we have “and their adoption tried.” It seems a shame to hear this fine word used in any other connection, such as “loyal to the gang”—“loyal to his confederates”—“loyal to the enemy.” It is too fine a word to be employed in a manner possessing the significance of the word “traitor.”

50 Now that the word loyalty has come back into such vast everyday usage, the time is ripe to nail it down hard and fast to the principles for which it stands. Why not say “he was in cahoots with the gang”—“false to his constituency”—“dishonest with his confederates?” Then, in our mind’s eye, let us hang the word loyalty alongside of the flag and keep it there for all time.

As I write this chapter, keeping in mind the subject of Making Life Worth While, a feeling of serenity pervades my inner consciousness. I believe that loyalty practically reigns supreme in America. I believe that the fifty-fifty variety has become scarcer than hen’s teeth when measured by the whole citizenship. Only among the unenlightened, the profligates, the misanthropes and enemy aliens, are they bound to be found at all.

51 Thanks to governmental efficiency during times most trying, the searchlight has been turned upon the meaning of the word loyalty in this country. The flag symbolizes it and it hangs everywhere. We take off our hats to it when we pass it on the street, and when we hear the songs that match it we join our voices with the rest.

To love the flag is a soul quality and when the souls of a hundred million strong go out in support of the Stars and Stripes there is mighty little standing room for the mere onlooker.

He is either with us or against us—that’s the slogan that thins the ranks of the unbelievers in our country. It makes them sit up and stare at the truth. It makes them blink their eyes in wonder, which is first aid in thinking things over. It causes them to look52 around and compare their standpoint with that represented by the Star Spangled Banner.

In taking stock of the situation here is what they found to be true—that this great country stands for peace—not only for itself, but its neighbors all over the world. That peace is so desirable, and so essential that it is worth fighting for to the last man and the last dollar. That without peace nothing counts as of value in the entire inventory of things worth while and, therefore, nothing remains but to fight—and to a finish.

When your Uncle Sam rolls up his sleeves preparatory to a scrap he begins to take on size that distinguishes him from the ordinary fighter. He goes about it methodically, and allows himself the proper time in which to get in readiness. Then he takes a running53 jump into the middle of the ring. After this the disinterested onlooker isn’t long in catching the fact that, as a mere matter of discretion, it is far better to be with Uncle Sam than to be against him. Also it must creep into his mind that if he doesn’t want to be smashed into a proper state of mind, the best thing to do is to join in and help.

If a hundred million people want peace bad enough to fight for it, both for themselves and their neighbors, it isn’t for slackers either in thought or in spirit to stand on the side lines and watch the scrap. People of that mould do not belong in America.

Everybody must do his part and do it right. There are thousands of ways of helping on toward victory. There is more than one way of fighting. The most potent of all is to back up the man who does—except,54 of course, when his time comes, every man capable of pulling a trigger must pick up his pack and take his place on the firing line. Meanwhile it behooves all of us to be ready for the call.

It will take more than a star shell to light up the pathway of a man who clutters his brain with half-baked knowledge. Pitfalls galore are ahead of him no matter which way he may turn. Such people are, by nature, of the cocksure variety, going in where angels fear to tread, and gaining nothing for certain by reason of their experiences. In time they earn the reputation of being bull-headed and sooner or later are on their way downstream without a rudder.

Sometimes the strong-willed fellow of fragmentary knowledge isn’t to blame for his affliction. Every little circumstance has58 something to do with his future course and if he happens to be born “on the wrong side of the moon,” his course is more or less predestined. He views things through a film—hazy-like, and inaccurate. To him investigation means nothing. His mind is like a sieve that will not retain the fine particles which must accumulate until a firm foundation forms upon which to bear a permanent housing for his reasoning powers.

The worst phase of the ever-ready reckoner of uncertain statistics is that he usually circulates among the credulous. Who of us is there that hasn’t at some time in our variegated careers sat across from him at an old-fashioned boarding house table d’hote? Even now we can hear him saying, “My notion of that is this!” And wasn’t it fun to watch those who drank it all in and gulped59 it down with their coffee? The green cheese story about the moon would have been swallowed by some of them if our half-baked know-it-all persisted in its truth.

For such as him, no doubt, was composed Kipling’s wonderfully cynical line, “alas, we know he never could know and never could understand.” And also for such as him it was ordained that he should never stay in one place long. Something tells him to keep moving—perhaps the giggling that breaks out in the midst of a lofty peroration; a snort of derision at some observation intended to be philosophical but which fell far short of the mark.

While it doesn’t take long to pack up and locate elsewhere, it must be tedious work to have continually the task on hand of making new friends—only to lose them. But that60 is the penalty of becoming the butt of the jokester, who will not be denied. Once he finds a victim it’s time for that victim to move. The jokester has no pity, and in lofty speech he tells his victim so—accompanied by shouts of approval from those who hear and understand.

The ego of ignorance which stands by its false assumptions from sheer lack of correct understanding invites pity that it seldom receives. In due course of human events the distributor of half-baked wisdom will be grafted with a twig from the tree of learning and thus the species will become extinct. This, as Shakespeare says, “is devoutly to be wished,” and while wishing it seems perfectly all right to express the hope that those who read this short chapter will make a point of sowing a few seeds in certain gardens where61 tall weeds now grow, “just for the lack of the rake and the hoe.” A little sarcasm will turn the trick.

To make life truly worth while one would, if possible, follow his natural bent, having trained himself accordingly, otherwise no matter how successful he might become in a material sense, regrets would be inevitable and likely to lead to a surly old age. It is a vast mistake to believe that the possession of great wealth insures happiness—and without happiness whose life is worth while?

The makings of many a good butcher, baker, or candlestick-maker have gone to waste when a youngster walked through the wrong doorway in search of his first job. That is the initial lottery ticket we buy—and sometimes pay for most dearly.

66 The situation is better now than heretofore, particularly if the youngster has, on starting out, the advantage of at least a high school education. To that extent he has a trained mind. If he could have gone on through college or technical school his success would be practically assured. To get through would mean that he had acquired proper mental balance.

Nevertheless, the great majority still go forth into the world of affairs with small educational equipment, just when their minds are least prepared, which accounts for the old saying—“a little knowledge is a dangerous thing.”

So, when John Henry Jones, the hat-maker’s son, shows a disinclination to go to school his father is pretty sure to take a shot at him something like this:

67 “Either go to school, or go to work. You can’t lay around and loaf.”

Now there was where John’s father got off on the wrong foot. There and then he missed his chance for a real heart to heart talk and at a time when his boy, from pure lack of reasoning ability, had worked his mind into a bad state. Then was the time to have dropped his tools and straightened out the kinks in the youngster’s noggin. A little friendly counsel might easily have shown the folly of going out into the world without brain tools to work with.

As for the boy, his whole future most likely hung upon the result of an interview inside the first doorway he entered. Not possessing a proper amount of mental training his natural tendency became his sole guardian at the supreme moment of his career—the68 start. Surely it would be a matter of luck how he came through. His future, in a sense, was in the hands of strangers and a strange environment.

In these days people are employed to fill a certain niche. If they fill it, they are allowed to keep on filling it. There’s little chance to look up from the job—and when the day’s work ends there’s little chance to look around for another. Thus if John Henry was set to work in a menial position at the beginning he might never be regarded as eligible for a position leading toward real advancement. He came without knowledge and for lack of opportunity he gained none. Being a perfectly good sweeper and duster he remained to sweep and dust until, in despair, he tries for a job at another place.

“But,” you say, “the example is not trustworthy.69 Look at the great men who started out in a small way. They are now the bulwark of the nation.”

Perhaps true, but times have changed radically. It is the boy graduate that is being sought after now. “Big Business” is bidding for the annual graduating classes long in advance. It wants trained minds to fill brain positions—and that’s why the college man and the graduates of technical schools forge ahead so quickly. They literally run over the half-educated, untrained workers who sit and wonder at their own lack of advancement.

It’s not a matter to pout about. There’s only one thing to do—work out of it. A special course in the thing the mind and talent is best fitted for is the way out. Why wait for “lightning” to strike us? Night schools70 abound in all branches of learning. Many a man has turned himself into a brilliant lawyer, expert accountant, or famous editor, through night school work. Diligence and perseverance is the price of success, and only through success do we find life entirely worth while.

I have received many letters from boys and young men who had read Laugh and Live, asking me to name the requisites for success. I have made but one answer to all such inquiries:—A healthy, clean body and a trained, clean mind. There is no other answer.

Some day I propose to write a novel!

The main reason for this determination is the fact that I have never written one. I don’t know that it will become a “best goer”—and the chances are against it—but I’ll do my best just the same. And I hope to win.

My reason for writing a fictional story is that by so doing I will exercise my imaginative faculties and thus prolong their usefulness. The power to imagine is an asset that must not be dulled by neglect. It responds to exercise just as readily as do the arms and legs.

Mental gymnastics are helpful, in fact74 they are absolutely necessary in keeping alert the upper story of the general structure. They make of the brain a spectacular trapeze performer toward which all eyes upturn when it takes its place upon the swinging bar.

The ability to write a successful novel would be a crowning achievement since it draws upon experience and vision in order to assemble interesting characters around an agreeable plot. Love, of course, must furnish the motif because love is the highest and most noble form of passion—and passion rules the universe.

When we contemplate the writing of a novel we indulge in aspiration of the highest order. The fact that not one novel in a thousand is likely to measure up to a masterpiece should not halt one’s determination to75 put over a winner if possible. But novel writing is big game hunting, requiring ammunition of considerable power—and the aim must be perfect.

One should try for small game first, being careful to make a bonfire out of every effort that will not stand the test of several months in cold storage. Real fiction can wait. It needn’t be served to order. Any novel that is going to live through one generation of applauding readers will keep a few months while its author uses the pruning hook. His judgment will be all the keener each time he goes over it.

When I write my novel I shall allow no close friend to read it in advance of its legitimate publication, after having been duly passed upon by a calm and candid professional critic with a beady eye. When one of76 these zest-worn individuals wades through my effort from first to last page and comes up smiling it will be time enough to indulge in a faint hope. It is always best for success to ooze in rather than to come as a deluge. It gives us time to consider ways and means of taking care of the output. Also it serves to ward off an aggravated case of disappointment if it doesn’t turn out to be a genuine gusher. We never know the real verdict until we hear from the multitude. No multitude, no verdict necessary—the book is dead.

It isn’t for the reason that I lack for things to do that I propose to try to write a successful novel, nor is my reason mercenary. There is no secret about the matter either. Some years ago I determined not to go through life with a single track mind. To obviate this calamity it dawned upon me that77 I must take an interest in every little and big thing that came my way. Once the resolution took the form of habit, it became a great pleasure to persist in the pursuit of information, but the main benefit derived has been the development of a determination to do things myself.

Determination stands in constant need of repair else it deteriorates into mere obsession and falls of its own weight. The habit of investigation builds up self-confidence, without which, determination has no prop with which to sustain itself.

Investigation is a two-sided activity of the mental processes—it comes in loaded and can go out loaded if there’s anything inside to facilitate the movement. To prove this theory is my reason for taking a fling at novel writing, and by succeeding my case is78 made. At least it will have been proved that one’s mind is a reconverter—that what it imbibes in one form it may exude in another. Also it proves that if one does not exalt his own ego no one else can do it for him.

Genius is twenty per cent idea, thirty per cent talent, and fifty per cent initiative. Ideas are small in themselves when reduced to brass tacks, but when we put the steam behind they often turn into something tremendous.

Even a fool may have an idea, but it takes brains and pep to put one over.

Most every one has had a notion worth while, but in most cases they hold it cheap on the theory that if it really amounted to anything some genius would have thought of it long ago and put it into practical use. There is where initiative was lacking—perhaps82 talent as well—but initiative would have brought in talent from the outside.

The word genius has been largely misapplied. Many men who were merely astute in one way or another have been placarded with the label of genius. But the real genius is one whose idea has saved something for his fellow man in time, labor, and money. Who would have thought forty years ago that the whispering cups which children talked into, and by means of which they could hear each other’s voices a distance of fifty or a hundred feet, would turn into the greatest labor-saving device in all the world! Such has been the fact ever since the telephone became an everyday utility.

The principle was discovered in a toy—the practical, every-day application as a labor-saving device was to come—but it came83 soon. A genius brought it about by inventing a transmitter which enlarged the sound waves when vibrated over electrically charged wires. Just as simple as water boiling in a tea kettle—which, by the way, led to the steam engine.

Steam, steel, and electricity!—the playground of the world’s greatest inventors—where genius abounds. Here were born our captains of industry, our fabulous fortunes, our empire building resources. Intertwined with these three great principles the super-genius has romped and played with nature’s secrets until the age in which we live is one of touch the button—and some labor-saving device does the rest.

We think it wonderful to live in the present age of genius. Nothing seems lacking. But what snails we’ll seem to those who come84 along a hundred years from now. Do we think that Arizona will lack for rain when she needs it—even fifty years hence? Surely the drudgery of the horse will have passed into oblivion. Mr. Ford to the rescue! Having taken him out of the roadway, he most certainly will not allow the horse to go on slaving in the plough field. That blessing is already in process of solution.

The real period for the genius is in the foreground. The hardships of the past are over. Capital is ready and waiting eagerly for the new idea no matter how small, or how big. Genius has but to shake off inertia, build up initiative and make full use of its talents. There isn’t a stumbling block in sight. The road is clear—and every added facility helps that much toward making everybody’s life worth while.

I’m for that hard-hitting type of manhood which stands adamant for the square deal and no surrender under all circumstances. It is one thing to wish for justice—quite another to stand up and fight for it.

Probably not one man in a thousand is geared with sufficient heart action to run counter to a false public opinion. It takes moral courage to do this, even on a small scale, whereas to ride a bucking broncho one needs physical prowess which is quite another kind of bravery. We’ve all known men who would fight their weight in wild cats but would run like a frightened rabbit at the88 sight of a pretty woman. To get up and make a speech would have been out of the question for them.

I heard of a case where a fine, quiet fellow who had been elected as a delegate to a small county convention, was instructed to arise to his feet at the moment of a certain nomination and shout “I second the nomination!” Instead of following instructions he fainted. This so excited the delegate who was to “move that the nominations be closed” that he forgot his part, with the result that an opposition candidate was quickly proposed, carried the convention, and, in due course, was elected by the vote of the people.

Men of the type of President Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt, each distinctly different in personality, are about as scarce as hen’s teeth. There are just two such men in our89 hundred and odd millions today. They stand unique in the courage of their convictions, and their ability to reach the boundary lines of public opinion over the world. Lloyd George belongs in the same corral.

Speaking of President Wilson, one is amazed at his perspicuity. In procedure directly opposite from Roosevelt or Lloyd George, he has no counterpart either in pattern or turn of mind. Everything yields before him—he appears to be indomitable.

The need of such a man at this hour is apparent. He asserts the rights of the nation as a whole in such a way that the individual trails in behind him without a quaver of fear or a compunction of conscience. The President seems to know the road and results bear testimony to the fact. In the shortest possible time he has mobilized the greatest nation90 in the world to a war basis of such magnitude that its martial tread extends around the world. This being the first globe-girdling war in all history, who can say that any other man would have done better—or even so well?

Fortunately, this country has another man who, in the absence of our present leader, could have stirred the American nation into action in behalf of its own security. Hardly need it be said that this man is Theodore Roosevelt. His distinguished services in the past would have proclaimed him the leader in such a vast enterprise had the emergency existed. Taking things as they are, his influence has been of tremendous importance in effecting a united effort. His willingness to go to the front himself at the head of a Volunteer Division had its own91 weight in determining the whole nation that the battle was ours as well as for those more adjacent to the fighting zone. But, to start with at least, this is a young man’s war, and the four sons of Roosevelt that went to the front constitute an ample offering from this great man at this stage of affairs.

If Lloyd George were a citizen of these United States, I’d give him a seat beside the President on the score of bull-dog tenacity. And I’d give him a look in on Roosevelt for brain activity and physical courage. And a seat between both of them for his ability to scorch the hides of the recalcitrants.

Three big men these—Wilson, Roosevelt, Lloyd George. They sit tight for what’s right. They stand exalted in the estimation of all right-thinking citizens of the world, and at this period of their lives are peerless92 in the beneficence of their influence upon mankind.

And now for the fourth man on my slate—stand forth General Joffre! Your initiative at the first battle of the Marne saved the world from disaster. You had one chance in a hundred and—you saw and you took it. Your victory saved civilization a colossal setback. Had your beloved France been forced to surrender, the dream of the enemy would have been transformed into fact with Mad Moloch in the saddle for many a weary year.

Here’s to the Big Four—long may they live to witness the gratitude of all mankind!

During one of my four-day jumps from coast to coast recently, I made the acquaintance of a very affable gentleman in his early fifties. He had the advantage of me in age, having passed through my period some twenty years back, while my advantage lay before me, yet to be disposed of. He was a man of brains, his eyes were alert, his years rested easily upon him. I marveled at his physical activity, also his mental pep. One thing he said to me that will hang in my memory the rest of my days.

“I am guided by my hindsight—you at your age, by your foresight,” said he. Then he went on to explain.

96 At my age he had ambitions and crowded on the steam. At forty his success in all ways seemed assured, so he rushed forward with all his might. At forty-five he experienced a period of physical reaction, which, in the light of his present knowledge, was a warning, but he did not heed it. At forty-seven he was a physical and mental wreck.

“I had failed to adjust myself to my failing powers,” said he. “I took on greater responsibilities than ever, bent, as I was, on rounding out a huge success. I almost wound up in my grave.”

Now here was a chance for a real pointer from a man of intellectual force, so I urged him to go on through the sequence of events that had brought him back to such superb health and spirits.

97 “It took me three years to get by that ugly period of mental and physical depression, the early part of which I spent in floundering around from one expert to another, traveling here and there and gaining nothing in the way of respite, to say nothing of cure. Then suddenly, I stumbled into an acquaintance with a new adviser—a life insurance agent!”

I broke out laughing at this point and he joined good-naturedly.

“I knew you’d be amused,” said he. “Every friend I have jokes on the subject. Nevertheless,” he continued, “this life insurance agent cured me and I haven’t taken a spoonful of medicine since I met him. Are you interested as to details?” he asked, his eyes twinkling, his cheeks glowing with health. (Courage, friend reader. This isn’t the beginning of the novel I intend to write.)

98 “Up to my ears,” I replied. “I am interested in every little thing that happens.”

“Well, it’s worth your while,” he continued dryly, “and the ‘cure’ may serve you well some day. I met this man at Long Beach. I was sitting under a large umbrella-tent watching the bathers and feeling like “Sam Hill,” when a fine, strapping young man came dripping out of the waves and sauntered up near me. It was a hot day and noting my ample shade he came over and looked down at me good-naturedly. I would have given all I possessed for his robust health and grand physique. I motioned to some unoccupied space under my tent, which he accepted.

“‘Not sick, I hope?’ said he enquiringly.

“‘Oh-no!’ I blurted back at him. ‘I’m feeling like a young kitten.’ Then I glowered99 at him ferociously. That made him laugh, and he was a good hand at it. I turned away from him in disgust, and let him do his worst. Finally he calmed down and quite soberly remarked:

“‘You’re not sick—nothing the matter with you! I’ll write a policy on you in a week’s time if you’ll do as I direct. I am a life insurance agent and I mean what I say.’

“‘I’ll take you up,’ I bellowed in reply, ‘and I’ll bet you five hundred you lose!’ I was pretty much exasperated at the fellow.

“‘You’re on,’ said he, ‘but I won’t take your five hundred if I win. Let’s put it this way—if you are well enough to pass a rigid physical examination one week from today will you let me write you up for a fifty-thousand dollar policy?’

100 “‘I will, young man, and you can start your shell game at your pleasure. But I won’t stand for any science work or nonsense. If you bore me I shall tell you so and that means all bets are off and you go your way.’

“‘We’ll begin now,’ said he quietly, but there was a certain air of confidence in his voice that made me wonder.

“‘First, I’m going to tell you about yourself,’ he went on to say. ‘You’re pretty much like an engineer who went along forty years without an accident and then his engine broke down and both went to the ditch in a heap. You’ve been successful in business, anyone would know that at a glance, but you’ve made a mess of your physical resources.’ I nodded. He was right thus far.

“‘You started in early at the game, your101 affairs grew, your responsibilities enlarged, and you worked your gray matter overtime without stopping to oil up your machinery. In other words, you have never played, you haven’t laughed, you haven’t mingled with people in a social way. So now you are pretty near ready for the scrap heap. Am I right?’

“‘Uhuh—go on,’ said I.

“‘You once came pretty near asking a fine woman to marry you, but something came up and you forgot it.’

“‘Yep—you’re right, Mr. Mind-Reader. Proceed,’ I said, ‘and whatever you do or say don’t mind my feelings.’ He noted the resentment in my voice I presume, for he waited some time before going on.

“‘The rest is easy—any life insurance agent who knows his business could take up102 the story at this point and go ahead with it.’ He laughed good-naturedly as I shrugged my shoulders.

“‘You’re an agent, go on with the case. What’s the answer? Let’s hear all of the horrible details.’ I was getting peevish, although the fellow had my interest aroused.

“‘Very well. Yours is the old, old story. At forty big things loomed ahead—your circle enlarged. You gave yourself up to big plans. They progressed famously and at forty-five you were a rich and influential man. But there were a lot of multi-millionaires that had you skinned on size of pile so you took the plunge and went after them. You never gave your waning physical powers a thought for the next two years, and then you went all to pieces—mentally.’

“‘Mentally! what do you mean when you103 say mentally? Am I crazy?’ The thought made me laugh.

“‘Mentally,’ he repeated with a good-natured smile. ‘You didn’t go crazy—your brain fagged. It wore out just like a typewriter ribbon wears out—from constant usage. You’ve been thinking ever since that your physical department was to blame for your condition. Nothing of the sort. You are in fine physical trim, or will be when you take your mind off of your ailments and forget about the old deals. Come on, let’s take a dip,’ he urged, and the first thing I knew he was dragging me along into the brine.

“To make a long story short, that fellow got me to laughing and playing like a boy. We violated every rule of health that had been laid down by doctors and in five days were playing golf together.”

104 “So he won his bet after all,” said I enthusiastically, for I had been pulling for the agent all through the recital.

“You bet he did, and I let him write me up for a half million instead of the sum he named.”

“Bully for you!” I replied. “And I’m going to remember what you have told me.”

“That’s right—at forty begin to adjust yourself to the next period—forty-five. Arriving there safely, begin to adjust for fifty. If you are alive then you should go on for years, always keeping in mind that you must readjust every fifth year after you cross the forty line.”

There is an old saying that you can’t fool a percentage table, and that was what the agent went by. So, if our lives are to be made worth while we must surely observe the105 simple rules governing health and longevity. The candle won’t burn at both ends and stand up in the bargain. At forty I’m going to begin to adjust—I believe what the agent said.

A college man not only wants his sheepskin when the great day comes, but his letters as well. To win his degree he must contribute to the sum of human knowledge—a man-sized job—considering the large storehouse already filled to overflowing. But the wreath somehow rests easier upon the brow of learning when Ph.D. or Ph.B. are safely tucked away among the laurel leaves.

Only the trained mind that delves its way successfully through college or university is likely to add to existing facts. The vast majority only succeed in developing a severe headache. Their intentions were good, but——

110 It isn’t so much the doing of the thing as the satisfaction of having done it.

My college career was cut short before my aspiration to excel took root. If I missed anything it didn’t occur to me then, but looking backward it has been only natural to regret that I didn’t stick it out and try for the honors.

But there are many other ways of making life worth while. Versatility wins more “heats” these days than originality. Ideas are worth little to the man who can’t put them over and are usually to be bought at bargain prices. Versatility and personality hitched tandem are certified winners before they start as against mere originality.

It is not given to all men to make a success in college. But there’s one thing certain,111 whatever the gain coming out of an attempt is that much to the good.

College life in itself, with all its joys and stunts, is a fierce competitor of the curriculum. Those who would win a degree must necessarily bone for it, never for an instant straying from the narrow path leading to the goal. Likewise it behooves them to keep both eyes glued upon a lucky star—for every little helps.

Somewhere in the “milky way” of admonition he is almost sure to come upon that famous old signboard, which reads like this:

“’Tis naught for sun to shine! Contribute thy share to the oceans of human knowledge—you can if you will.”

I must confess that this bit of poetic advice112 made a deep impression upon me. It seemed to urge me on but not to the same extent that other matters urged me off. It is a good little verse just the same and worthy of a hook in anyone’s memory. Aspiration, perseverance, never-give-up-the-ship-stick-to-itiveness is the way the prescription reads for those who would plant so much as a mustard seed of original information in the garden of wisdom.

As I have stated in my foreword, this book is not intended to adhere to any fixed plan. I am writing on subjects covering a wide latitude, many of which have been suggested by questions out of letters written to me by friendly spirits who like my picture plays. Although the facts relating to my theatrical career have been published over and over again, hardly a day goes by without receipt of letters on that subject.

The prevailing notion is that I come from a theatrical family and that I was educated for the stage. Nothing is further from the truth. My father was a lawyer with116 a knowledge of the drama such as few professionals have had. From the time I was able to eat I was fed on Shakespeare. When I was twelve years old I could recite the principal speeches in most of that gentleman’s plays.

My article in Photoplay some months ago gave the whole story in fewest words and the same is herewith appended.

My dramatic education was augmented by frequent contact with great actors. My father was a friend of Mansfield, Edwin Booth, Stuart Robson, John Drew, Frederick Warde and other famous actors who were his guests whenever they visited Denver.

I once asked Mr. Mansfield about the best way to prepare for the stage and he told me that there was no such thing as preparation117 for the stage; but that there were certain accomplishments that were essential to great success. These included a knowledge of fencing, painting and the French language. Modesty precludes a discussion of the result of following that advice. Suffice to say, I can defend myself fairly well with rapier or broadsword, I can tell a Corot from a Raphael without the aid of artificial devices, and I have made my way through France without being arrested or going hungry.

Writers who give advice to the ambitious usually cite experiences from their own book of life, but if any young man were to follow in my footsteps, he’d take a rather devious path to the stage and he’d have to travel some.

My parents were far from convinced that I was cut out for the stage, so I was sent to118 the Colorado School of Mines to become a mining engineer. But there didn’t seem to be any room in my head for calculus, trigonometry and such things. I could never master higher mathematics; therefore I could never be a mining engineer, so I quit.

Now I’m not desirous of inflicting a recital of my deficiencies on a magnanimous public; just trying to show that one may fail in many things before finding one’s niche in life. Certainly I failed in many ventures, even in my first attack on the American stage. The first onslaught didn’t even make a dent on that historic institution.

Important results have often hinged on trivial things. Tiny causes have had titanic effects. If a certain actor hadn’t been sent to jail in Minnesota a dozen and a half years ago, I wouldn’t now be writing this.

119 If you are familiar with baseball—and the chances are nine in ten that you are—you know the meaning of the expression, “the breaks of the game.” Given two baseball teams of equal strength, victory will invariably perch on the banner of the side which “gets the breaks.”

It’s much the same on the stage or in business. Many a good player has been sedulously avoided by whatever fate it is that deals out fame, because the “breaks” have been against him. Conversely, many a mediocre—or even worse player, has tasted all the fruits of victory because he “got the breaks,” as they say on the diamond. But don’t think I’m going to classify myself, because I’m not. Give it any name you like—even modesty.

Just where I would have wound up had120 it not been for a strange quirk of fate, of course no one can tell, but it was the misfortune of a fellow player that gave me the big chance I was looking for. Perhaps it was an indiscretion rather than a misfortune. But whatever it was, the victim of the circumstance found himself in jail on the day we were scheduled to treat the natives of Duluth, Minn., to a rendition of “Hamlet.”

Now I’m not going to tell you how the star couldn’t show up and I stepped into the breach and soliloquoyed all over the stage to the thunderous applause of the Northmen; that would be too conventional. Strangely enough I hadn’t set my sights that high. But I did want to play Laertes and my colleague having run afoul of some offense which was the subject of a chapter of the Minnesota Penal Code, I played it that night.

121 Well, to make a long story short, I played the part so well (?) that it only took about ten years more to become a star on Broadway, the ultimate goal of all who choose the way of the footlights. Seriously, however, that was my chance and I took full advantage of it.

Perhaps the greatest pleasure I get out of my work for the screen is contained in the daily mail bag. Letters come from everywhere, not only this country, but from such far-off places as Australia. By the way, I believe they are more enthusiastic over the screen in the Antipodes than they are in this country, proportionately speaking.

One of the most frequent questions I am asked to answer is that relating to success in athletics.

It may sound strange to some of those who have been following my work on the screen,122 but I was a failure as an athlete. In college at the Colorado School of Mines I did not excel in any particular branch of sports. I went in for nearly everything, but the student body never wrote or sang any songs about me. I never came up in the ninth with the score three to nothing against us, with three men on base, and put the ball over the fence. I never even ran the length of the field with the pigskin and scored the winning touchdown with only fifteen seconds of play left.

When I went to Harvard later I still was active in athletics, but while just about able to get by in most of the games, I never got the spotlight in any specific instances. It might have been different had I remained, but the call of the footlights was too insistent.

There is one rule which every athlete must123 follow to be successful. Be clean in mind and body. For a starter, I know of no better advice.

I am not much given to preaching, but if I ever took it up as a vocation, I would preach cleanliness first and most.

The boy who wishes to get to the front in athletics must adopt a program of mental and bodily cleanliness.

Perhaps the greatest foe to athletic success, among young college men is strong drink. Personally I have never tasted liquor of any sort.

It was my mother’s influence that was responsible for that, as I promised her when I was eight years old that I would never drink. I might state, parenthetically and without violating a confidence, that my family tree had several decorations consisting of124 ambitious men who had sought valiantly, if futilely, to decrease the visible supply of liquor. I do not wish to take a great amount of credit for my abstention. Really, more credit is due to a person who has fallen under its influence and fought his way out; but I know that the keeping of my promise to my mother has had a powerful effect on my life and my career.

Everything depends on something else. There is no such thing as absolute independence, and those who think differently are simply asleep at the switch. Of all things sought for in this world happiness stands first, and to be sure of this estatic state of being the common mistake is made in selecting the path supposed to lead most directly thereto.

Wealth—choice No. 1. The common error of the human family.

Wealth is the great destroyer of happiness, for it breeds discontent and worry. In the first place comes the worry of accumulating128 wealth and once possessed of it comes the worry of hanging on to it. It is but a step from worry to discontent.

But take away the doubt, for the sake of argument, and analyze wealth from the standpoint of possession. Now that we have wealth let’s go ahead and enjoy it. Let us make of our lives an elysian dream. All right, here goes.

But first, just what is an elysian dream? Answer—an elysian dream is most quickly defined by the word naught. It is a figure of speech and only useful in poetic flights—no transfers issued. The iridescent dream is the nearest high-sounding vagary that can be bought for cash and that has a rainbow finish. It soon fades and is lost from view.

So we come quickly back to the proposition that wealth, while useful to the stomach129 and the back, has no purchasing power with the soul. Happiness is a soul quality—how to reach it is a quandary.

Of things earthly we only require a certain amount; an overplus takes away zest. The sport of the hunt is no more, when the quarry is tied up by the heels. Anticipations are happier far than realizations. When we aspired we looked forward, and up. When we indulged to the full our eyes fell to the ground.

“The fun of gettin’ money is the gettin’ of it, son.” This line is the wind-up of a wild Western solo one of the boys in camp used to sing with banjo accompaniment. That is all I remember of the song. It struck me as funny and also as being gospel truth. After having satiated one’s utmost desires, every luxury seems trivial and vain. Anticipation,130 which is a species of joy, no longer dwells in the heart. Thereafter we hunger for the unattainable—contentment. Very seldom do we change our ways when we have waxed fat and soft—and money won’t buy everything. Note the “if” in old Aunt Dinah’s Camp Meeting ditty:—

And there we are, blockaded with a measley “if.” There are things that money won’t buy—for instance, a good night’s sleep. Our “open sesame” to the higher level is via the Self-Denial line. Money won’t buy a ticket—only the good and faithful servant may pass through the turnstile.

Paraphrasing a well-known song to fit a new emergency one of my good friends, on learning the title of my new book, sends the following lines which he hopes may find a place in Making Life Worth While. And so they shall, with many, many thanks to the contributor.

There is a wonderful pathos in this lyric.134 Al Jolson, in a serious moment, could put enough soul stirring melody in the last line to bring an audience to its feet. And wouldn’t “Rodey” make a Billy Sunday meeting fairly ring with it?

There is more than sentiment in the verse quoted—there is duty, loyalty, fidelity. Our boys have a right to expect that nothing untoward shall be allowed to disturb their dear ones while they are absent, and that whatever the misfortune to themselves over there, the welcome home will be whole-hearted and genuine.

If ever there was need of cheerful sympathy, the genuine article, it should come forth now for distribution among the homes from which husband, son, or brother has gone forward in defense of civilization. One need not fear to show an interest, which is heartfelt,135 to any wife, mother, father, or other relatives of an American soldier. It is a relief to them to share their hopes and fears with friendly neighbors. They are brave as they never were before. They are fortified by the spirit of the manly fellow who went forth to war through the very gate you lean upon as they tell what they know.

One very dear mother, much too young in appearance to suggest the idea of having sent a son to the front, told me as she smiled through tears that he had brought down two in a single action, but unfortunately was forced to land on enemy soil and was made a prisoner.

“I hope they don’t starve him,” said she sweetly, “nor treat him cruelly. He is so gentle and kindly himself. I believe they will be good to him.”

“Of course they will,” said I, joining my136 hope with her own and wishing with all my might that I could really share in her belief. Then her wistful look changed into one of confident expectancy. I had added to her store of hopefulness and left her laughing heartily at my prophecy that her boy would probably “kidnap his guard some night and ride him back to camp.”

No doubt about her keeping the home fires burning, nor of the strong heart within her—“hoping, longing, calling for him.”

This word super is getting its name in the papers every day in the week. The super-human effort required to keep things moving along toward the final triumph has needed just such expressive terms. It is a last word in inspiration—big, effective—over and beyond—and it fits the job we’re engaged in exactly from super-dreadnaught to super-abundance of will-power, mainstrength, and get there.

When our boys went over and lined up alongside their war-worn Allies, the whole situation changed. The pep and snap they brought along completely banished the waning140 spirit which, nevertheless, still held in check a relentless and overpowering foe. No tonic is there so productive of renewed energy as the entrance of a friend who quietly takes his place by one’s side.

To merely say that the boys in khaki have won the hearts of their comrades over there is inadequate. They have sealed a compact that is destined to shape the orderly course of the whole world for a century to come. Their induction was not of the “make way for the conquering heroes” kind. Nothing like that—more of the fashion of those who are tardy and quietly take the places reserved for them.

Once in the ranks, comradeship was a matter of course. No one could hold out against American good nature. No chance that these new soldiers ranging themselves alongside141 of veterans would resort to grandstand play. There would be no chasing after the medal. If it came, well and good, but the job in hand would be the first consideration—and in that respect the men of the Allied armies and navies are well met.

To my way of thinking the every-day athletic sports of the English-speaking races make for a gallant hardihood. No braver are they, but hardier perhaps, and more agile than their Latin brother-in-arms because of their all-of-the-year-round season of out-of-door recreation. Baseball, golf, hockey, polo, motor-boating, rowing, skiing, football, riding to hounds and what not, even down to the game of marbles, which, after all, is out-of-door exercise for the small boy.

Take football, for instance. If medals of142 honor were given out for daring physical action and bravery that occurs on the “grid-irons” of America, England, Canada and Australia each year even the Kaiser’s Iron Cross factory would be unable to supply the demand. In other words, out-of-door sports make for alertness of mind and body. In this respect they differ from the labor of the soil which, while hardening and muscle-making, is inspiriting from lack of competitive prowess with a goal in sight to work for.

It is fine to read about our boys over there. They have taken hold of their end of the big job without splurge or pompous bearing. They have aroused no jealousies, no heart-burnings through competitive ambitions—they go where sent. Their inborn initiative spurs them on to deeds that terminate to victories they least expect. It is not a part of their dispositions to “grab all” for honors.143 They will give rather than take from the credit of their comrades in arms. The old charge of American brag will fall of its own weight on the battlefields of France. To excel is an American trait no less and no more than their brothers in the field of action. One of the blessings that must surely follow in the wake of the great slaughter will be the common understanding that every Allied soldier did his duty like a man.

Since writing this chapter, I came across an editorial in the New York Evening Telegram, which backs up my theory exactly. It reads as follows:

“American soldiers and sailors have won the hearts of England and France. ‘I like their keenness,’ said a pain-racked British sergeant through his bandages. ‘It’s good to be fresh and alive to every little happening for you and your boys who can plunge144 into hades for the first time and keep their heads. You may be sure they will go a long way.’”

At Hamel, where the Americans went in with the Australians, Lucien and ’Arry and Paul and Tony and Pat and Izzy stood shoulder to shoulder, one loyally helping the other. The commander-in-chief of the Anzacs, Lieutenant-General Sir John Monash, is a Jew. Hovering over our fighters were an aviator from Fort Wayne, Ind.; one from New York and another from Nogales, Ariz.

Of a surety, as Kipling sang:—

Mighty powers are at work in the world today. Mighty changes are taking place within the depths of our natures. We are not satisfied with the old order of things that have trailed along with our opulent years. The great holocaust of war has sobered our senses and we find ourselves taking stock of the past with particular reference to the future—the near future we hope.

We are thinking of the day when the boys will come back home and we have it in mind to tidy up considerably by the time they begin to arrive. We believe they will approve of our work, and unless they do we may as148 well look the situation squarely in the face—they’ll do some cleaning up on their own account. They’ll finish the job.

The order of the day is change. There are old, worn-out labels that must give place to new ones, particularly one which has outlived its usefulness, entitled—the inherent rights of man. It needs revising. Its by-laws must be revamped, recast along modern lines in order that liberty shall not be mistaken for license nor any man claim immunity on the assumption that because this is a free country he may do as he may please.

When the boys come home they are going to ask for an accounting. They will want to take more than just a peep at our stewardship. Where are the loafers hanging out? They’ll ask us that. And they’ll ask about the dives and dens and thief-making sports149 that boldly flaunted themselves in the days before the great change.

A lot of the boys won’t come home. They’ll be asleep, over there, but the big majority will return and they will be men of brawn—resolute and brave. They will begin at once to ask questions that will make some of us wince, and they are going to insist upon truthful answers. “What about the profiteers?” They’re going to insist on knowing all about these fellows. They will seek them out and compel them to disgorge their ill-gotten gains—profits taken from the families of these men who crossed the seas to rid the world of just such a piratical crew.

And what about booze—have we given that traffic the final punch? If it wasn’t good for soldiers to fight on how could it be useful in civil life? These are questions150 we’ve got to answer when the boys come home and it looks as though we were going to be able to give a good account of ourselves—thanks to the government.

Things are changing—many things have already changed. The big crucial tests upon our national conscience are coming to a head. Our government is far-seeing and alert. Abuses still exist, but the eyes of able men are upon them. A government that is capable of sending millions of men under prime conditions to foreign lands in behalf of our most precious rights need not be expected to fall down on the task of cleaning things up at home while they are away. The whole world is to be made safe and clean, including the U. S. A.

When the great war broke upon an unsuspecting brotherhood of fellow humans, we were, as a nation, from prosperity and self-indulgence, perilously near the brink of disaster. It is only in the light of events and a backward glance toward the precipice which had yawned for us that we may now indulge in a certain sort of solemn consolation. At least, we have been saved from a worse fate, one that has bells on its toes—our national intellect was on the wane; likewise our national conscience. But we were not alone—all nations were afflicted, ours no more than the rest, but we were the younger and more opulent.

154 Regeneration or degeneracy? That was the uppermost question in the public mind when the king of Berlin turned loose his hosts of degeneracy, thereby bringing back to its sober senses the brain power of civilized mankind. And with it came the brawn.

Now when brain and brawn hook up together the danger of getting stuck in the mire is well nigh impossible. Men who had gone sordid while amassing great fortunes and looked on passively while their families cut the swath to which wealth and position seemed to entitle them, jumped to their feet with a new light in their eyes, while men just entering upon the threshold of success stood in awe of consequences beyond their control. But the main thing to happen was that the world turned its face toward the great intruder and, thereby, its heels toward the fatal155 abyss into which millions would have fallen from sheer crowding from behind.

We had been following the modern tendency and had gone the limit in quest of that will-o’-the-wisp called pleasure—which we never quite found. We nearly did, or thought we surely would, but in our hot pursuit we heard the blast of a war trumpet and we stopped in our tracks!

The weakest link in the chain of self-gratification had broken—the War Lord and his hosts had gone stark mad! Now was the time for the cohorts of insanity to wreak vengeance upon the joy-seeking, peace-loving people of the world. We who were on the brink of another kind of pitfall—too much opulence—paused in awe and horror to gaze upon the oncoming hords. And right here began the regeneration of mankind.

No one, taking the larger view of the156 world’s greatest catastrophe since the flood, will hesitate to believe that, even unto its most horrible detail, it represents the working out of some great plan. The world was far better off after the flood, for when the waters receded it was found that the valleys had been enriched by the washings from the mountain-sides and the hills. A new virginity had entered into the soil, the future value of which, to mankind, being wholly beyond computation.

And so in the final reckoning this tremendous letting of blood will have long since shed light upon its true significance. To-day we estimate it upon the basis of its horrors, its seeming uselessness, the blight of its trail across our own dooryards. But we’ve all heard of the fungus growth which blights the157 progress of plants and trees; and parasites which destroy the grains of the field, bringing famine upon the population. In the present case the tentacles of the great Octopus of Degeneracy took such strangling hold upon the body politic that half a world seems doomed to die that the other half may live in aid of the great plan of the universe. In the meantime, no life is worth while that takes no part in the titanic struggle, which must go on and on until, in the words of our leader, “the world is made safe for democracy.”

By DOUGLAS FAIRBANKS

—containing especially chosen chapters from his famous book “Laugh and Live.” Each booklet contains 32 pages, printed on paper of extra fine quality; also a special picture of the author never before produced.

LIST OF TITLES

1. Whistle and Hoe—Sing as We Go

2. Taking Stock of Ourselves

3. Initiation and Self-Reliance

4. Assuming Responsibilities

5. Profiting by Experience

6. Wedlock in Time

| Boards, Illuminated (boxed) | $0.50 net |

| Leather (boxed) | 1.00 net |

Britton Publishing Co. New York

Punctuation, hyphenation, and spelling were made consistent when a predominant preference was found in this book; otherwise they were not changed.

Simple typographical errors were corrected; occasional unbalanced quotation marks retained.

Ambiguous hyphens at the ends of lines were retained.

Redundant chapter titles have been deleted from this eBook.

The first uncaptioned illustration represents the cover; the other uncaptioned illustrations are semi-decorative line drawings of the author.